A hobo encamped at a Lower East Side gallery, surely a casualty of the Great Depression. Photo collage by Kenny Schachter.

Just before coming to New York for last week’s art fairs, someone tried to sell me a Louise Lawler that had been marked “Lost Property” by an auction house—a sign, if ever there was one, that there’s too much art in world. So much so, in fact, that some people simply forget to pick up what they’ve paid for, as if the mere act of acquisition was enough—and the act of shipping and living with the work wasn’t worth the effort. Or even storing it, for that matter. A very First World problem.

In any case, the fact that there’s such a glut of art in the market makes art fairs akin to software update reminders—they’re a constant annoyance, but you fear what you might miss if you ignore them. As Bjarne Melgaard recently posted, “Art fairs suck but I saw Ryan Michael Ford at Spring Break and I just really love his paintings.” That says it all: a necessary evil but there’s always something to see, even for the most impervious.

Everyone is an Insta-critic these days. I particularly emjoy the work (and opinions) of Bjarne Melgaard. Image courtesy of Kenny enhachter.

So, what constitutes the farrago of fairs known as Armory Week? The Armory Show was launched by Colin de Land, Pat Hearn, Lisa Spellman, Paul Morris, and Matthew Marks in 1994 in the Gramercy Park Hotel as the Gramercy International Art Fair before moving to its twin piers on the Hudson River in 2001 (in the same building where I took the exam to qualify as a lawyer in 1987). The New Art Dealers Alliance (aka NADA) began in 2002, VOLTA in 2008, the Spring/Break Art Show in 2009, and the Independent art fair in 2010. I’m probably missing a few others that have also squeezed into congested New York, but you get the picture. I actually did the Gramercy and Armory fairs in the beginning, before being unceremoniously dumped, but that’s another story.

New York gallerist Lisa Spellman—who initially opened on Park Avenue in 1984 before subsequently decamping to the East Village, then SoHo, and now Chelsea—has been prescient in her practice from the beginning, working early on with luminaries (today, not when she started) Robert Gober, Vito Acconci, Karen Kilimnik, Doug Aitkin, Christopher Wool, and Collier Schorr, among others. She is a longtime hero of mine and was even married to Richard Prince when she first launched her gallery—how cool is that? I asked Lisa a few questions to get a reading on how things have changed since the inception of the Armory Show, and also to sound her out on whether the widely reported crunch being experienced by small and mid-size galleries is any different from the hardscrabble times of the recessionary early 1990s.

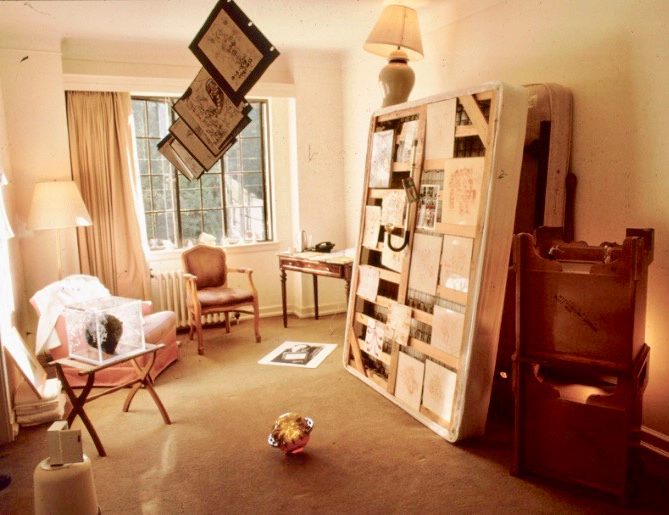

Where it began, the proto-Armory Show known as the Gramercy International Art Fair in the mid-’90s, here with an installation by Rachel Harrison. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

According to Spellman, there are salient differences that make it hard to compare the ’90s with today: “The cost of real estate was still cheap then, and there are more predator galleries now.” But have the pressures been exacerbated, or have the stakes materially changed for today’s galleries?

“Hmm, that’s tough,” she responded in an email. “Maybe there’s more pressure now? I mean, I had several jobs to keep the gallery open early on and taught and that all seemed normal and fun to me! Plus, it was the New York renaissance of artists coming to the city and a nexus of music, fashion, and art then, so the pain of financial Armageddon seemed worth it. The NY community was supportive, but I think artists and galleries have more support now. And, most works we sold were $2,500 to $12,000. Now, $50,000 is the new $2,500.”

The long-running 303 Gallery—indeed, I’m a fan! Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Lisa saw other bright spots on the horizon too, even when it comes to fairs. “Small fairs are the future!” she enthused. “The Indy (Independent Fair) was the closest experience to sleeping in my room at the Gramercy first year.” There you have it in a nutshell, from someone who knows: things generally aren’t any worse, and perhaps even better, than in decades past. Of course it’s still a struggle to be a small or medium-sized space—it always was and forever will be—but, simultaneously, there are more opportunities, especially for artists, than ever before. Starving dealers may be the new starving artists, though.

Speaking of starving, the Armory charges $47 for general admission, $65 if you want to throw in a trip to VOLTA, and $80 if you want to come back again and again over the full run of the fair (lord knows why). If you happen to hail from out of town and want to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art while you’re at it, you might need to take out a bank loan.

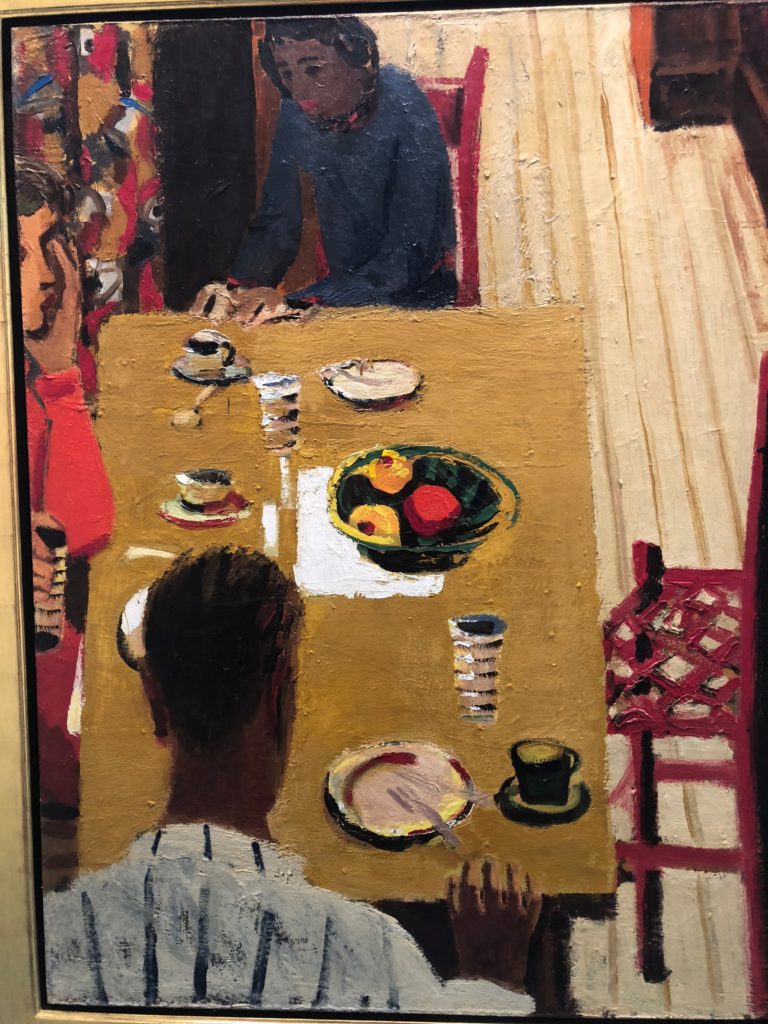

It’s a sport to clock how many gallery principals you can spot still manning their booths a day after the openings (spoiler: there are far fewer than at any given Basel). Gauging participant feedback covers the gamut from slower-than-last-year to sold-out stands—and there’s no shortage of sniping between fairs and dealers alike. Fun, indeed. One way not to worry (too much) about business is to not offer anything—the NFS (not for sale) booth tease, which was the case with the knockout space of San Francisco’s Hackett Mill Gallery, featuring painterly paintings by Milton Avery and David Park. Slightly confounding in such a strictly commercial context, but, hey, I’m happy to benefit from a rare instance of gallery largess.

David Park’s Table With Fruit (1951-52) at Hackett Mills’s NFS Armory Show booth. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Los Angeles’s Nicodim Gallery hosted a compelling solo outing by 28-year-old Simphiwe Ndzube from South Africa, but the gallery might have benefitted from adhering to the drug-dealing credo espoused in Scarface: “Don’t get high on your own supply.” The sold-out affair was powered by scenesters the likes of Benjamin Lee Ritchie Handler, self-described “gallery director, actress/model, and DJ,” who snapped up a piece. When I requested images, they accidentally sent me Simphiwe’s waiting list for paintings. Add me to the list.

I thought I managed to survive my first fair of the week without consuming anything, but was mistaken—I forgot I had purchased a little work (on the layaway plan, of course) prior to the onset of the Armory. It’s a 1973 painting-on-board by 97-year-old Wayne Thiebaud, from Allan Stone gallery. I had seen the work in September at EXPO Chicago (formerly Art Chicago, which began in 1980) and it caught my eye (again) in the pre-show PDF I received from the gallery. My deposit ensured it stayed out of view at the Armory when it came to New York.

Ninety-seven-year-old Wayne Thiebaud’s Three Cigarettes and a Cigar (1973). Courtesy of Allan Stone Gallery.

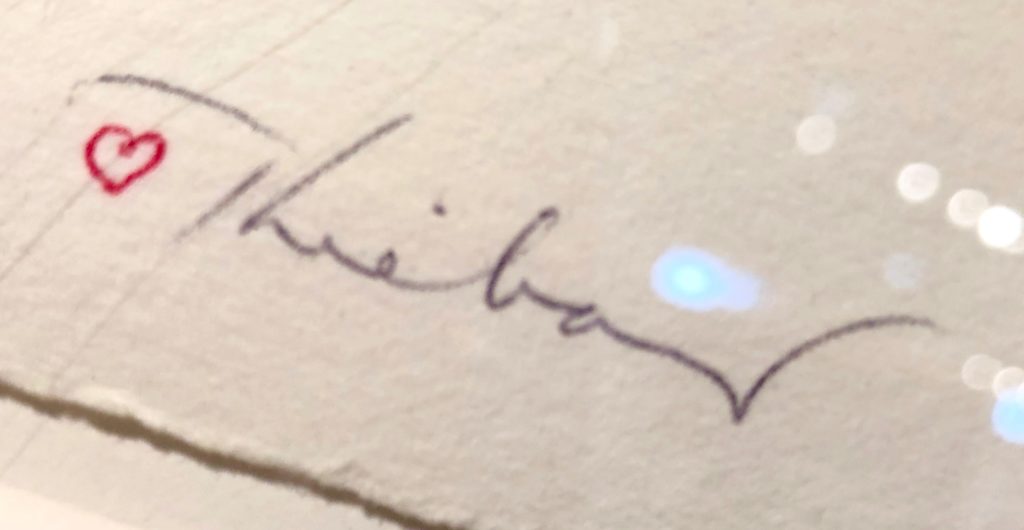

Only I could cotton onto the least Thiebaud-looking Thiebaud imaginable, the opposite of the confectionary treats that delight most: a collection of three smoldering cigarettes and a cigar. Though I never had a habit, I am a sucker for art with smokes. Thiebaud has a heart for art, intermittently signing his works with a tiny red doodle, refusing to explain to anyone who asks him why. Very cute! PS: Thiebaud’s auction record is for a relatively recent 2005 work featuring a pair of slot machines that sold for $6,325,000 at Christie’s in New York in 2013.

A heart for art: Thiebaud intermittently signs his works with an adorable doodle and won’t say why. What a cutie. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Spring/Break was a messy affair not for the short-attention-spanned, and my concentration levels resemble a flea these days. With art strewn willy-nilly over two floors of the disused Condé Nast office building in Times Square, it was always going to be a losing battle with the melodramatic midtown views. There were more artists on hand than you could shake a stick at (scary thought, that), many of them squeezed into the micro-booths and competing with what was on display. I was mouthing a steady stream of what I thought were inaudible opinions under my breath; but, to the mortification of my kids (who were in tow), I was mistaken. They were forced to yank me out of certain booths before I crossed the threshold, prophylactically, to save face (theirs). But, seriously, this type of hybrid fair with an equal measure of participation by curators, dealers, and artists—pocket-sized, agile, and out of the ordinary—will continue to be vital and appreciated more than ever. Except by me. I’m kidding.

The Spring/Break Art Show as experienced by Kenny Schachter: a vision of flaming hell. Gif courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I was embarrassed when I realized I missed an artist I set out to see at one or another of the fairs. But part of the reason I won’t slather on the descriptions of last week’s slate of events is that, with Instagram, you can get a better notion of what transpired with a quick scroll through the image app—especially if you follow another one of my heroes, the New York Times’s Roberta Smith, who still renders me speechless after all these years, as she did with her shorthand precis on Independent. (I’m in such awe of her that she’s brought me to tears before—imagine that. It was in 1991, when she scolded me for trying to talk to her while she was viewing one of my first curated shows.) In a pinch, though, any of the other more-plugged-in-than-me grammers will do.

The fair machine marches along unabated (even more so in March) but the full-on surfeit is beginning to have a deadening effect. One dealer compared participating in the Armory to attending a mass Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. For me, it was like Groundhog Day, an endlessly repeating treadmill of tedium. I felt dissociated from the proceedings much of the time, making me think I need a new shtick. Dealer Jose Freire created a showy, two-part brouhaha on Artnet about quitting fairs altogether and, honestly, I don’t blame him. It reminded me of the campaign to promote responsible gambling standards: “When the fun stops, stop.”

Good advice! Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

So, should I stop, take a break? Nah—it hasn’t come to that yet, nor will it anytime soon. But you do need to pause and reflect. Of course, I’m off to Beijing gallery week in a matter of days and then Art Basel Hong Kong, so I guess the pause is on pause. And then, in April, there’s MiArt in Milan and Art Cologne. That’s the tune I march to—it’s my fate, so no more complaining. I’ll try. And, if I end up, as most dealers will, in hell, I know what it will look like: the Spring/Break Art Show.