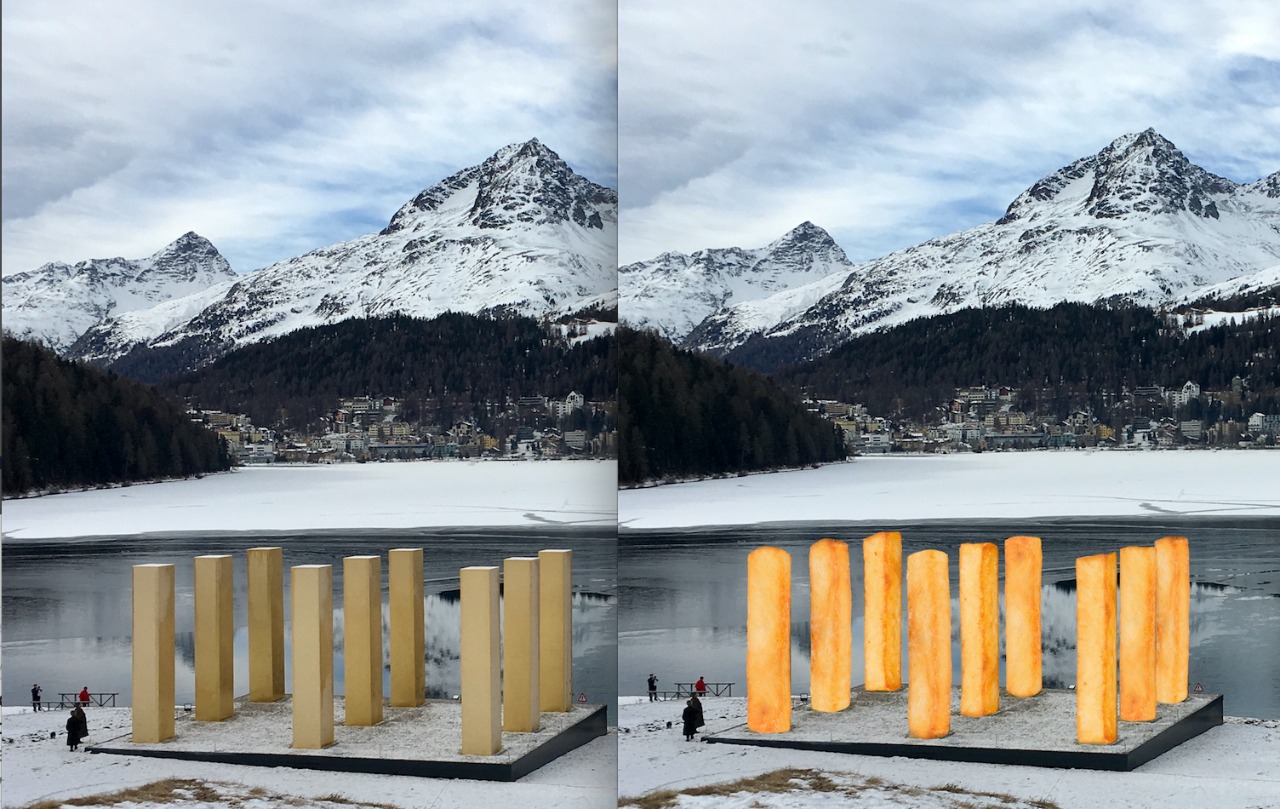

The Sky Over Nine Columns by Heinz Mack, with illustration by Kenny Schachter.

Writing in St. Moritz, Switzerland lands me on a slippery slope in more ways than one, besides accidentally smashing onto the pavement on occasion. After an article I wrote last year, I was chided (and social-media-blocked) by the wife of a long-time resident and former gallery owner with the following admonition: “The death of dealers is indiscretion.” And I was under the impression I was being laudatory and reverential.

This, in turn, instilled a hesitancy to simultaneously post my impressions of the handful of gallery shows that dot the bustling alpine village while still sharing my holiday with the participants of the story. There is a degree of familiarity with the fur-and-jewelry-clad community that return for decades throughout generations.

Life in the art world is like a Bildungsroman, a novel of formation and education where there is an enduring amount of information to absorb. In that regard, St. Moritz is about the most perfect place to take a family ski vacation, if you have as much an aversion to skiing as I do.

Who knew? Everyone who wins a Pulitzer gets a free horse. Photo illustration by Kenny Schachter.

There is a Christopher Wool text work that reads: “THE HARDER YOU LOOK THE HARDER YOU LOOK.” And in St. Moritz, that can translate to the more you see, the more you see. There are not many resorts in the world that have such consistently high quality gallery-going in which to engage.

On the downside, St. Moritz has worse diversity stats than any iteration of Art Basel. The crowd is as white as the (artificial) snow—there seems to be less and less of the natural variety the past few seasons, though the coming days are expected to see the coldest weather of the last century, go figure. There is conspicuous ostentation (often involving masses of deceased animals) that would make a peacock blush. And if you have a thing for rejection and self-flagellation, apply to one of the private clubs that you (and more so, me) would surely get rejected from; they wait with baited breath for the opportunity to do so.

The bars are like cramped airport smoking rooms (I didn’t let that impede me) even though puffing is illegal in public places. A friend joked they could tell the time of night according to how crooked the glasses were on the bridge of my nose. But if you can’t beat them, try and get some of their caviar (I read it was at one time prescribed as an anti-depressant)—unless you have to pay, that is.

After violently careening down the famed and notorious Cresta bobsled run a year ago, this year I opted instead for long hikes and hand-feeding the tame Engadin Coal Tit birds between art tours; and, demonstrating typical Swiss efficacy, there are packets of seeds in dispensers along trails. The eager birds are only too happy to appease tourist Insta-fools. Why isn’t feeding collectors as easy?

The town centers around Lake St. Moritz where horse races, entitled “White Turf” (it certainly is), have been held on the frozen lake since 1907. From fluctuating temperatures turning the ice into a vibrating membrane, sounds reverberate like chanting whales.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, Attesa at Robilant + Voena. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Public sculpture is often a compromise (or losing battle), especially pitted against such a heroic natural landscape. Just off to one side of the lake, The Sky Over Nine Columns by Heinz Mack was installed. Produced in Italy, mounted in Dubai, on view on the lake in St. Moritz, the 2014 sculpture is comprised of 850,000 24-carat gold leafed mosaic stones, is 7.5 meters tall, and weighs 50 tons. The privately-owned artwork is a long way from work of the austere Zero Group that Mack and Otto Peine founded in the late 1950s.

It reminded me of Walter de Maria’s Lightning Field with the steel poles replaced by giant, thick-cut French fries (in need of some Heinz ketchup). On a more serious note, it begs the question of whether public art becomes an obstruction/distraction in the face of such beauty. Now on the third leg of some kind of promotional tour, I can imagine its ultimate destiny back in Dubai in front of a shopping mall. I’d rather see an acid colored Franz West twisted penile form for a dash of fun and frivolity.

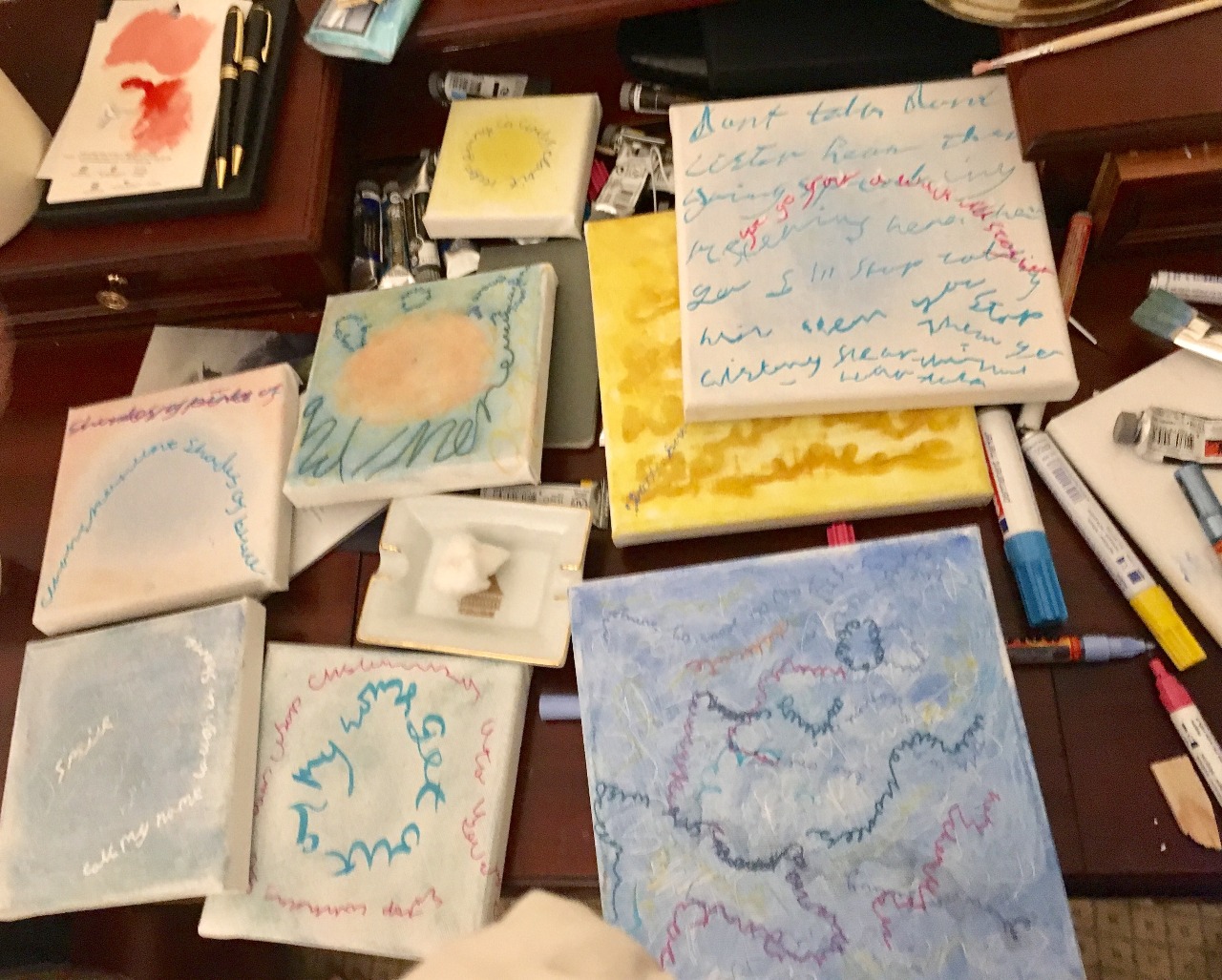

Kai Schachter’s little paintings. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Stefan Hildebrandt had to leave the space he’s occupied the past few years, and instead, like an art refugee seeking shelter, took up temporary quarters in a fully functioning (Christmas-decorated) church. As I’ve previously stated, Hildebrandt, who typically displays somber, monochromatic hybrid works from the 1960s through today, is a dedicated foot soldier who always has something to say, and it’s never what anyone else is saying (or doing). For that, I have great admiration.

Presenting a one-person show by deceased German painter Raimund Girke (1930–2002) is no easy task to undertake, considering such a narrow market—though the artist just made an auction record of $87,000 (on an estimate of $30,00–40,000) at Grisebach this past December. The question is, could it transcend such a regional audience?

Raimund Girke at Stefan Hildebrandt Gallery. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The canvases were thickly painted striations from the 1990s ranging from €18,000 to €106,000. And though Girke was described by Hildebrandt as a pioneer painter of white (a seeming running theme), his paintings were all predominantly blue.

Andrea Caratsch, who has left Zurich altogether and is solely based in St. Moritz, presented a Swiss painting show where the artists and works were connected to the region. The show (which is up through February 4) opens a window onto lesser known artists and relationships, from Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899) and his son, Gottardo Segantini (1882–1974) to Giovanni (1868–1933), Augusto Giacometti (1877–1947) and Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966).

The title of the monumental Segantini, Primavera sulle alpi or in English, Springtime in the Alps (1897), brings to mind the fictional Springtime for Hitler musical from Mel Brooks’s famed film The Producers. But I’ll leave that association alone.

Segantini, Springtime in the Alps (1897), at Andrea Caratsch Gallery. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The painting last came to auction in 1999 at a twentieth-century art sale at Christie’s, New York, with an estimate of $4 million–6 million, and made $9,572,500. Now on sale for a whopping $38 million, it’s not as far-fetched as it sounds as it only represented a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.96 percent over the course of the eighteen-year ownership period, and chances are the net will be well shy of that. The work was expressionistically kitsch by way of Jackson Pollock, LeRoy Neiman, and Zeng Fanzhi; in any event, it was still a revelation and most major works are in museums including the Segantini Museum in St. Moritz—I tried to visit but they keep unorthodox opening hours.

I dipped into Robilan + Voena with its show, “From Taddeo Gaddi to Lucio Fontana,” on view. The Fontana was vacationing in St. Moritz after a fall appearance at Frieze Masters in London. I sheepishly asked one of the principals which Old Master was the best—okay, the most valuable—to which he bellowed, “Anyone could see!” Er, anyone but me, apparently. It was the Gaddi (1300–1366) panel, which was going for $2,500,000 and had an auction record of $2,138,089, set in 2011 at Christie’s London.

Lake St. Moritz. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

In 2004, I visited Jeff Elrod’s (b. 1966) studio prior to his participation in a group show curated by Rita Ackermann and Lizzi Bougatsos called “Indigestible Correctness,” which was staged in a short-term space I operated in New York’s West Village. Jeff pointed out that he met Christopher Wool at the time, who was also in the exhibition and who went on to become an extraordinarily close friend and supporter of the artist. They both have studios in Marfa, Texas.

It could be said that it’s a safe bet to present the mid-career painter at Vito Schnabel Gallery, where the show is on view through January 22nd, for the gallery’s second season in St. Moritz. Elrod is represented by Max Hetzler in Berlin, Luhring Augustine in New York, and Simon Lee in London. This pretty much means nearly everyone in town is familiar with the work and in particular, the blur paintings on display. (He said these will be the last of the series.)

The range of hypnotic hues was expanded, more so than in the past, which created a steadily intensifying narcotic effect. If going to this show after too many gin gimlets in the Kulm Hotel across the street from the gallery, view at your own risk.

I liked the works in blues and greens in addition to the black and white combinations he’s previously explored. He’s an American Albert Oehlen with the interweaving of digital imagery applied employing his brush wielding digits. The works were punchily priced between $200,000 and $350,000, with several said to have been sold. Elrod’s auction record, for a blur painting sold at Chrstie’s London in 2015, is $343,607.

Back in 2004, Elrod’s work entitled Fallout was priced at $14,000 and Christopher Wool’s P432 and P436 were $70,000 and $75,000 respectively, none of which sold at the time. The record today for a comparable abstraction by Wool is about $4 million. Go and find another sector with similar such performance.

Trading off the Giacometti franchise was one Enrico, born in 1952 and potentially as related to the family as… my pug, Gremlin. Besides being known for well-crafted window fittings and chimneys, Enrico also creates riffs of Alberto’s most noted works, from 5,000 to about 40,000 CHF. Trying to find anything on the internet about the artist, I only happened on his website with another unconvincing attribution, this time linking him to a prominent local gallery and thanking them for presenting his pop-up gallery show, which they didn’t. He’s certainly wily.

For the first time in nearly 25 years I’ve visited, there was a police cordon set up at the mountain passageway, one of the few entry points into St. Moritz, flashlight-ing the face of every vehicle occupant. I must agree, 2016 was as tumultuous as I can remember and what’s next is literally anybody’s guess. During New Year’s dinner, we distributed questionnaires that covered politics, the art market, and family matters: the survivability of Trump, Mark Grotjahn, and which son will soonest make me a premature grandfather, a subject to be readdressed next year.

I dined with more than a few rabid Trump supporters during my stay. Looking at the incoming cabinet, if you plugged in a few Bloomberg terminals in the White House, you’d have the dream team hedge fund start up with a strong whiff of Goldman about it. And although entangling his kids in the office he has yet to assume smacks of wrong, I would do the same. I guess I already do, and Kai and Adrian made some fine little paintings in their room. Fingers crossed that there’s no residual cleanup backlash.

What are some forecasts? Will art-ificial intelligence come to the fore where software learns and anticipates; imagine you could black-box auction trends foretelling who is on what trajectory with which kind of works. You might combine the breadth of knowledge of Roberta Smith, Clement Greenberg and Janson’s History of Art: call it Clemetina. What’s even more worrisome was an email seeking work “making political statements” and a commission to write about art specifically dealing with refugees, it’s becoming a dogmatic knee-jerk, and aesthetics are typically the first casualty of such a period in art.

We spend so much time arguing for or against this, that or the other thing/person, I see people drawing nearer each other out of compulsion due to the unpredictability of world events as much as compassion. The St. Moritz sun set so brightly I was temporarily blinded, I find art can have a similar impact. But we all have to be hallway monitors ever on alert; forget the age of anxiety, rather we are entering an epoch of nervous breakdowns. But through it all, the art market will prosper if for no other reason than the lack of viable alternatives. And a dollop of hope I’d hope to believe.