Dealer (1999)

“Art world gadfly” is the phrase I use in my syllabus to describe Kenny Schachter (American, b. 1961, Queens, New York). His commentaries in Artnet News and other journals are required reading, and it is for his perspective on contemporary art and its markets that I have invited him to speak to my students these past two years. His lectures are a tour-de-force. Accompanied by meticulously prepared PowerPoints, he chronicles and analyzes his experiences, whether it is the London art market, participating in the Felix Art Fair in LA, or being grounded because of a pandemic. Thinking back on these information-packed presentations, I realize that they should be categorized as a component of his extensive and rarely commented upon body of art work. Although Schachter is best known for his multi-hyphenate role as a dealer, writer, Instagrammer, and hoarder, I have now come to the conclusion that all these activities should be subsumed under the umbrella: artist. Another epithet that is appropriate is amateur in the eighteenth century sense the word: lover of art. In all his work—written, oral, or visual—Schachter’s immersion in the today’s art world is unapologetic. Schachter eats, breathes, lives, and dreams art.

Money Money Money (2021)

Recently, Schachter has been a vocal promoter of the easily misunderstood digital form of the Non-fungible Token (NFT), expressing his advocacy in print, in his videos such as Money Money Money (2021), as well as in his minting of NFTs. In many ways, these blockchain trackable digital works are the perfect medium for an artist who has found visual representation through the manipulation of imagery since the early 1990s. In an environment that puts a premium on the MFA, Schachter’s formal training has been a JD, and, in his characteristic self-deprecating manner, Schachter frequently emphasizes his wide-eyed (often literally) enthusiasm for participating in what is reductively called the art world. He sells the work of other artists (Eva Beresin, Josephine Messer, and Mil Imeraj among others), calls out those who take advantage of credulous collectors, or investigates the whereabouts of the most expensive Italian Renaissance painting sold at auction. To those who follow his (ad)ventures, the imagery that accompanies his writings or his Instagram posts, can mistakenly be seen as simply illustrations, a sidebar to his sometimes manic, but always clear-eyed, accounts. I am guilty of just such a misperception.

Gremlin-Richter (2017)

Art Peace (2018)

It is the work Schachter contributed to the show at Filo Sofi Arts in Cranford, New Jersey—or rather his Instagram post showing the works hung Salon style—that forced me to reconsider and to spend time studying his visual productions. The digital prints and animated video Schachter contributed to this group show entitled Waiting… (curated by Kourosh Mahboubian) have two primary points of reference. Either they incorporate icons of postwar art or they place art world personalities in extreme positions. In the former category, Gremlin-Richter (2017) and Art Peace (2018) stand out. The still from an animation of the same title juxtaposes Gerhard Richter’s Betty (1988) with the doleful eponymous lap dog sitting on a red and white patterned textile that echoes Betty’s signature jacket of the same color combination. The references multiply in Art Peace: Robert Gober’s Untitled (1991) together with versions of Louise Bourgeois’s The Couple (2003) and Bruce Nauman’s bronze hands combine to form the arms of a peace sign. As examples of Schachter’s representation of art world movers and shakers, You’re as good as your last sale (2018) shows Loïc Gouzer, the boy wonder of themed auctions, nonchalantly arm-wrestling a determined Amy Cappellazzo; Adam Lindemann, Amalia Dayan, Iwan Wirth, Daniella Luxembourg, and others are playing sardines…in a sardine tin (Hotel Basel, 2017); Jerry Saltz sits awkwardly astride a perplexed but gentle grey steed in an art fair tent, weilding his latest article in the place of a lasso (Jerry at Frieze, 2018). These tongue-in-cheek digital prints (some of which Schachter has also produced in animated form) provide viewers an opportunity to prove their art historical expertise or art world VIP recognition. Schachter assumes his audience is as familiar with the canon of modernism and the current cast of art market players as he is.

You’re as good as your last sale (2018)

Hotel Basel (2017)

Jerry at Frieze (2018)

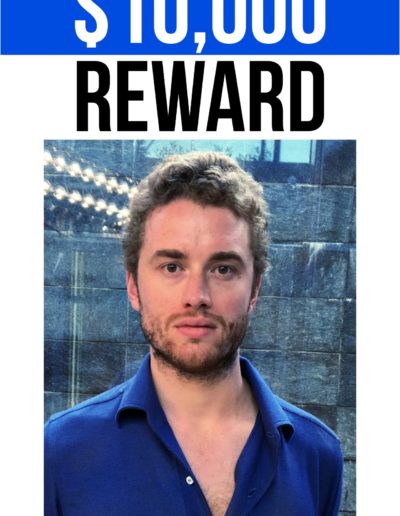

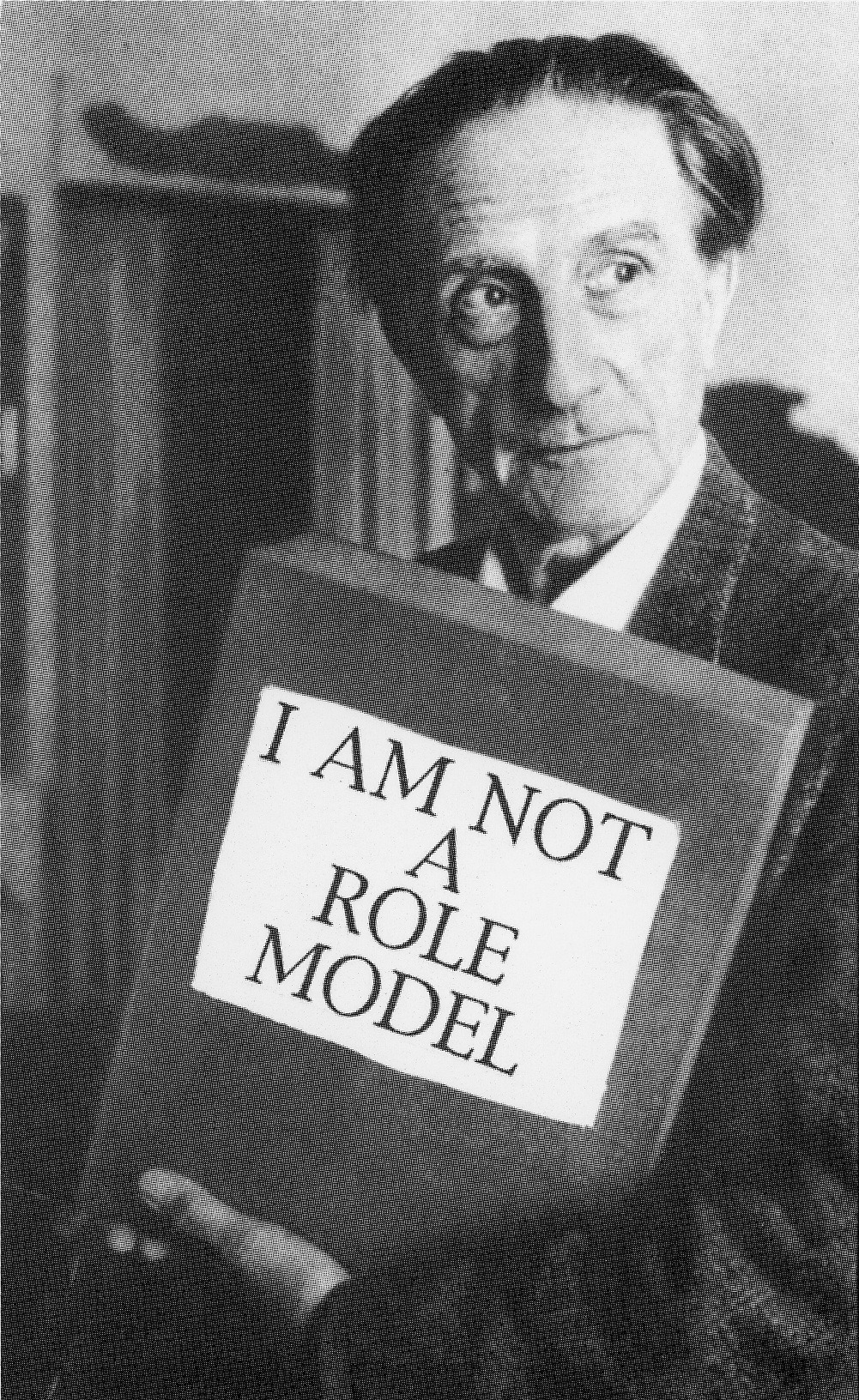

These works should be a treasure trove for the future art market historian. Taken as a whole (and conveniently on Schachter’s website they are presented chronologically by year https://www.kennyschachter.art/), they constitute an index of the issues that have made headlines any given year—fears over the transmission of Zika at Art Basel Miami Beach (see Zika Miami Basel, 2016), Alec Baldwin’s suit against Mary Boone over the misrepresented Ross Bleckner painting (see Boone Bite, 2017), the record-breaking sale of the Salvator Mundi in a contemporary sale at Christie’s (see Christie’s Blues Brothers, 2017), and several dedicated to the outlaw Inigo Philbrick (see Wanted and $10,000 Reward, 2019). Fearless in his skewering of art market darlings such as Damien Hirst, Richard Prince, Wade Guyton, and KAWS, Schachter is equally upfront about his inspirations: the very first work on his website (1993) features Marcel Duchamp: a grainy black-and-white photo of the provocateur in later life carrying a sign that reads “I AM NOT A ROLE MODEL.” Duchamp’s precedent as a disruptor of art world pieties is at the heart of Schachter’s body of work.

I am not a role model (1993)

Yet, Schachter’s work is nowhere to be found in the standard accounts of digital or internet art, such as Christiane Paul’s Digital Art (Thames & Hudson, 2015, 3rd edition) and her recent edited volume A Companion to Digital Art (Wiley, 2016), Rachel Greene’s Internet Art (Thames & Hudson, 2004), or Julian Stallabrass’s Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce (Tate, 2003). In many ways, Schachter’s digital prints do not fit the contentious definitions of either digital, internet, or net art. Thus, while his commentaries—written and visual—rely upon his access to and intimate knowledge of the contemporary scene, the absence of his work in academic treatments of his chosen medium ensure that Schachter is essentially an outsider, a position that he himself acknowledges in his self-representation. And just as Schachter’s chosen uniform are well-worn Adidas track suit bottoms with a slightly fraying cashmere sweater, the low-tech production values are, in fact, a conscious choice.

While his satirical, pointed jabs at the contemporary art flavor of the month or the self-serving social networks that might artificially prop up an artist’s commercial value can be seen as visual commentaries on what is frequently portrayed in the media as an unregulated market plagued by venal, if not outright illegal, exchanges, it is in his depictions of himself that Schachter is at his most poignant and potent. Tick-Tock (1998), a thirty-minute homage to Bruce Nauman, zooms in on the lower half of Schachter’s face—sometimes we see the rims of his wire-framed glasses, sometimes just his mouth—and records him emitting chirp-like vocalizations. This and other early videos are both allusions to his knowledge of the work of cutting-edge artists and records of a young initiate experimenting with a medium that simply requires a camera and lack of inhibitions.

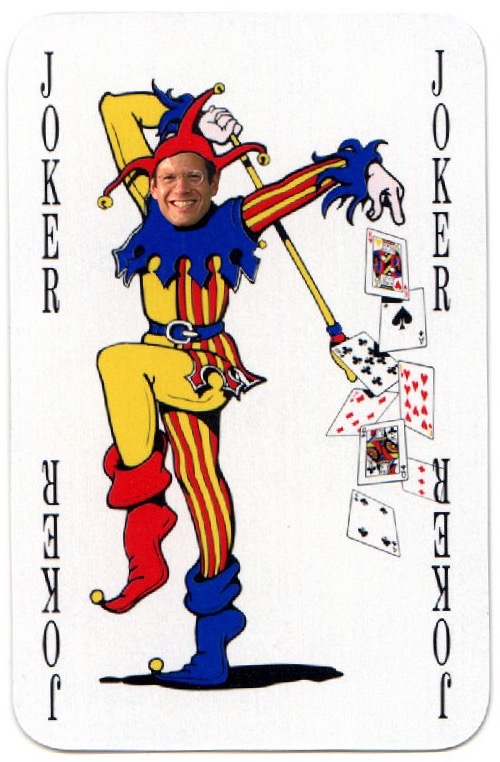

Schachter’s signature wire-rimmed glasses are once again a prominent feature in Dealer, a profile self-portrait, of the following year. Another grey-scale image, the title derives from the word inscribed on his right cheek. Calling to mind mug shots (a form he employs twenty years later in his “wanted” posters of the embezzler Philbrick), Schachter plays on the multiple associations of that word. It is not the image of a prominent, jet-setting art dealer. Rather, the monochromatic palette, the branding on his visible cheek, the intensity of his gaze, and the intellectual pose implied by those glasses simultaneously send a message of exposure and concealment. That aura of seriousness which underlies this early self-portrait is absent from his 2015 pair Court jester Kenny and Kenny joker where he inserts himself into an Erroll Flynn movie and onto a playing card. The unwavering, unsmiling gaze of his 1999 self-portrait is replaced by an impish grin and the shrug that is now widely known through his cartoon avatar; his wire-rim spectacles remain

Court jester Kenny (2015)

Kenny Joker (2015)

Schachter’s identification with those symbols of corrective vision is so strong that he includes them on bronze portrait bust that accompanies the one video on view in Waiting…. Ironically called a “death mask,” the allusion to mortality is carried over into the two-minute 23 second video Money Money Money in which Schachter both in the form of the death mask chorus of one chanting the refrain of the title, and in an animated full length, wearing his recognizable casual outfit, raps about the furor over what he calls the “NFT divide.” Situating the rise of the NFT within the context of digital art pioneers such as Nam June Paik—indeed the eternal connection between art and cold hard cash (or in this case bitcoin and etherium)—Schachter chides the viewer to accept this new form of expression (and currency).

Mosquito Kenny (2016)

The allusion to Socrates’ social critic with which I began is intentional (and not just because Schachter has portrayed himself as that mosquito responsible for the spread of what now seems as a relatively harmless threat—see Mosquito Kenny, 2016). As we learn from his Rap Sheet (Feb. 2021), Schachter studied philosophy in college. The program of his gallerist, Gabrielle Aruta, draws upon her own background in the discipline, and, in a recent conversation, she explained that she sees his work as grounded in a philosphical discourse. Endemic to the promotion of NFTs and the blockchain more broadly is the appeal to authenticity and uniqueness, a seemingly contradictory position to the appeal of the digital, or the infinitely reproducable.

While the practice of connoisseurship as formulated with the rise of the secondary art market in the sixteenth century and developed in the following centuries might seem at odds with the computer-generated art of the twenty-first century, both NFTs and the connoisseurship of Abraham Bosse, Jonathan Richardson, or Giovanni Morelli reveal an ever-present anxiety over how to evaluate works of art when livres, guineas, lire or now bitcoin are involved. One thing is clear, however, Kenny Schachter is unique.