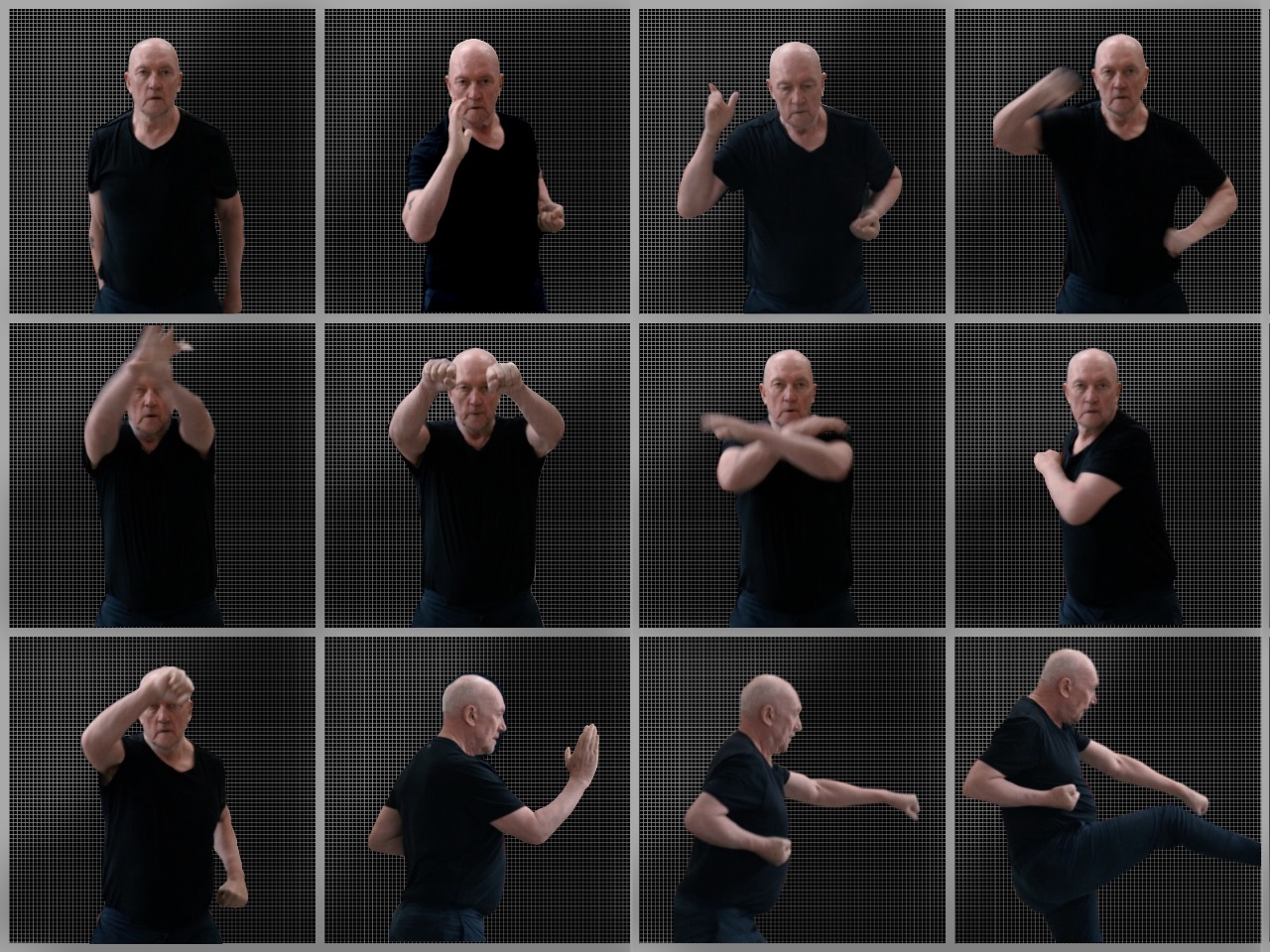

Street Fightin’ Man: Sean Scully as Muybridge study in motion. Collage courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

This is a review of the April 2019 BBC film Unstoppable: Sean Scully and the Art of Everything. Last fall I reviewed The Price of Everything. What’s next, The Everything of Everything? Directed by Nick Willing and produced by Michele Camarda, the Scully documentary is billed as follows: “A year in the life of abstract artist Sean Scully, one of the world’s richest painters. Little known at home but a superstar abroad, Sean flies around the world to open 15 major museum exhibitions—a journey that also reveals his extraordinary life story. Contains some strong language and upsetting scenes.” I’d say.

Of late, Sean Scully’s signature stripes have shed their formal rigidity and color constraints and now benefit from looser compositions—they’re literally slapped-on, as demonstrated in the film. Don’t get me wrong, I am warming up to Scully’s recent work and so is the market; there has been a slow but steady increase in the prices of his paintings, with all but two of his 10 highest results occurring within the past two years for works largely made over the last five years. (His current record stands at $1,692,500, from a 2017 Sotheby’s day sale.)

Only one small mid-1980s painting is slated for the upcoming New York May auctions, at Sotheby’s day sale, where it carries an estimate of $300,000 to $400,000. Though, if I was in the market for some stripes, I wouldn’t hesitate to buy a Mary Heilmann instead, whose paintings Scully’s more relaxed, liberally colorful works have—sometimes indistinguishably— grown to resemble, and who’s auction record stands at a shamefully undervalued $250,000. Or, as an alternative, I’d look at Stanley Whitney, whose auction high stands at $223,665 out of only 15 pieces ever offered publicly at auction. All three artists are of the same generation, born in the 1940s.

In the film, Scully is seen on his PJ (private jet) within the first two minutes and then over the next hour and a quarter proceeds to rack up more miles than Jay Z and Beyoncé on a world tour. The plane, which Scully proudly announces is his own, co-stars in the film almost to the point of upstaging the artist himself. You may have heard of the Instagram account Rich Kids of the Internet—perhaps there should be a Rich Artists of Instagram as well.

#globalexpress and #stripes #currencyofstripes #printingmoney. Image collage courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

As far as his significance as an artist, the only thing more hagiographic then the pronouncements of the critics, curators, and dealers featured on Unstoppable (one writer points out that Bono calls Scully “the bricklayer of the soul”) are the words and actions of the artist himself—which end up being less revealing about his work’s place in the history of abstraction than they are about what people will do if given the chance to hoist themselves with their own petards. No one gets off unscathed; I have six single-spaced pages of juicy, endlessly embarrassing quotes, but I’ll spare you the pain. I do recommend you watch it for yourself, particularly if there’s a chance you might yourself become the subject of an upcoming TV program (or journalistic article, for that matter). It’s a cautionary tale: the documentary plays more like an art-world reality TV show.

The program is as much about Scully as it is symptomatic of a media- and celebrity-saturated world, and of our proclivity to stuff a foot (or two) into our collective mouths whenever a camera (or recorder) is switched on. Yes, we are all complicit in a culture of oversharing, but if we can’t rein in ourselves somebody should step in and do it for us. (Everyone should have a personal editor.) In one scene, Scully is depicted painting in a barely-there Speedo. As Popeye (someone Scully could certainly identify with) might say, after a while the plane pix and unrelenting aggrandizements are more than a little embarasking!

The hardscrabble story of a street kid growing up piss poor, pulling himself up by his bootstraps while fueled by nothing more than steadfastness and sheer self-belief is admirable and inspiring. To drive home the point, we see Scully solo in one of his lavish studios doing energetic karate kicks and jabs, then we see him in another studio fighting an imaginary enemy, on that occasion armed with a big wooden stick. Yet he appears no more threatening than an overgrown, cartoonish version of the Karate Kid.

Say’s the artist: “I couldn’t be discouraged, the same way as Martin Luther King or Bobby Kennedy. They believe so much in what they believe they don’t mind if they get shot and I don’t mind either.” (I can see the headline now: “Artist Gets Shot for His Take on Stripes.”) Scully goes on to relate that, when he was a young man, he had to be a gang member and criminal if he wanted to stay alive. In a fit of road rage he barks, “I’d like to get that fat fuck out of his car. I’m aggressive enough for New York.” It is said that Scully needs a battle on his hands to thrive—no wonder he’s flourishing in the art world, since the same applies to most artists and dealers.

Museum directors, curators, and gallerists don’t fare much better in the film. Hirschhorn chief curator Stéphane Aquin boldly states that Scully’s name has become a sort of brand, an icon in and of itself: “People see Scully like Warhol or Van Gogh. That’s quite unique for an abstract artist. To have risen above the fray to become an icon is quite unique—a spokesperson for all abstract painting.” He might also have taken note of Malevich, Mondrian, Pollock, Rothko, Kandinsky, Klee, Mitchell, and Frankenthaler, not to mention living artists like Oehlen, Bradford, and (Cecily) Brown.

At one point, Colin Wiggins, a former curator at London’s National Gallery, says that the artist that Scully wanted to engage with in the museum’s collection was J.M.W. Turner. Here’s Scully on the subject, talking about the Romantic painter: “Do you think he’s still gonna be famous though, after the exhibition? I mean, you don’t think the public will turn against him when they see his work up against mine? You don’t think the public will say what a bad influence you’ve had? No, they’re gonna say these paintings by Scully are so simple even I could do it. Which is what I said about Van Gogh.”

Rich artists of Instagram featuring Sean Scully. Collage courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

And Scully didn’t just stop at Turner and Van Gogh—an artist and friend says our hero once declared “I will be as famous as Matisse.” In Scully’s own words: “My idea was to be as famous as Bonnard, and now I’m only as famous as me.” This kind of chest-thumping machismo and obsession with fame is heard throughout the film. You would think the paintings themselves were no more than a ploy for celebrity.

Ann Bukantas, head of fine art at Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, mentions that Scully approached her to do a show then bantered at the opening, “I sent you a painting for your collezione”—Italian affectation his own—”in the post. It will arrive with a stamp on it. I didn’t insure it—it’s only worth half a million dollars.” (Hope she reported it to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs department for tax purposes after the BBC airing.) When the question arises of whether the artist would be satisfied with the catalogue for the exhibition, Scully says, “I hope so. And what will we do if I don’t? I suppose I’ll just have a tantrum. But you’ll be alright with that, you can roll with that.”

Mnunchin gallery’s Sukanya Rajaratnam, whom I have the utmost respect for, contributes, “We have a network of very prominent collectors—perhaps the most prominent in the world—and when we endorse an artist people take our word for it. And typically two, three, four, five paintings in a group of 12 to 15 in a show may be for sale. And that’s why I joke Mnuchin is a museum with price tags.” And how do they decide which works can be sold? “He [Scully] tells me. I beg, he gives.”

Rajaratnam continues: “When I first met Sean, he told me I want to be the greatest abstract artist of my generation. And I thought this is a lot of hubris”—just like saying we only sell to the best collectors, and they listen—”[but] I didn’t know him then and I believe him now.” Harry Blain of Blain Southern, a friend I admire and adore (sorry Harry), chimes in: “You need to have museum curators, critics, and collectors visit an exhibition, so you offer everyone free food and drink in a nice location and they’re going to come to that. That’s what we do as a gallery.” There you have it, in a nutshell.

Dealer and curator Oscar Humphries, another friend (uh oh), curated a 2018 Scully show in Mexico City. “When I imagined the show I could see pictorially—you know, his sculpture against the pink wall—what an impact it would have, and how perfect it would be for Instagram,” he says in the film. “Social media is very important now and certainly on a personal level I have that in mind when I’m doing projects… how it will reproduce digitally.” What discerning curatorial criteria. On the same subject, the Hirschhorn’s Aquin points at a group of paintings and lets loose: “Well, they’re like framed for iPhones—that’s smart.” This gives great hope for the museology model in store for us. Say cheese.

The “Unstoppable” Sean Scully documentary contains some upsetting scenes of a very boastful, self-aggrandizing artist. Screengrab courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Scully was Ai Weiwei’s teacher at Parsons in his formative years—should we blame Scully then?—and the Chinese artist says in the film: “He abused me so badly, so bad, but I will not talk in public [about] all that happened.” Did he teach him anything? “He disarmed me,” Weiwei replies. “He’s an artist, he’s not really a good teacher.” At which point Scully, who is standing right there, is reduced to a bout of facial twitching, the first (and only) vulnerability in his on-camera armor. Could it be masking some inner insecurity and diffidence? Scully retorts, after recomposing himself, “I told him not to make paintings. I saved his life—he would have been a shit painter.” Weiwei responds: “I obeyed. I didn’t know what he wanted to do, make me like a bum?”

Weiwei also relates the experience of dropping into Scully’s studio back when he was a student: “Nobody buying piles of paintings lying in the studio. I could have bought for a few thousand bucks… ah, I missed a fortune. I never knew he was going to become like this.” He then says the paintings back then were better than the ones Scully is producing now, and then proceeds to apologize, to which the master says: “But you know what? He doesn’t have to say sorry. I don’t care. I basically don’t care what he thinks at all. Why did he say that? How the hell do I know. Why do you think he said that? It would never occur to me to analyze that. I don’t care enough.” Further along in the film Weiwei attends an opening of Scully’s despite his disdain, another fame-monger who can’t seem to pass up a photo op.

In closure, Scully himself sums it up nicely. “The story of my life is so emphatically written,” he says. “My success is now like a fucking runaway train. I’m the Donald Trump of the art world. I have his chutzpah.” No shit! Besides a just-opened exhibition at Lisson’s New York branch, his first at the gallery, he has yet another institutional show in Venice running at the same time as the Biennial. It’s entitled “Human,” but perhaps it should have been called “Superhuman.”