Step right up. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

When I began my career, art fairs were still in the Paleolithic Age. The marquee events were Chicago (really), Cologne (really), and Basel (can you recall when there was but one?). That’s it. In a given year, attending two of the three felt like a chore. Today, the utter transmogrification of the fair landscape is complete: there are too many to count and it’s not unusual for galleries to do between five to 10 per year. That’s a lot of frequent-flier miles, and time spent away from families. If there was a convention of fair directors, it would fill an expo hall. Before our eyes, there’s elemental change underfoot. Fairs represent the dramatically truncated attention spans of the Instagram generation (pretty much all of us by now), and the move away from the traditional gallery model of art consumption.

It must have been 15 years into my career, if not more, before I actually bought something at a fair. Now I can’t stop, though I also make a point of patronizing galleries at their real-world locations too (and not auctions). Bemoan it, throw your arms up, whatever—time will tell if something other than a trade show or app will replace the old-fashioned gallery-going experience. The fair flare-up is a symptom of the changing state of the economy, and how we see and experience art. Video killed the radio star and iPhones killed everything else: books, newspapers, magazines, music, and TV too. Are brick-and-mortar art galleries next?

I touched on this in my last column, but galleries have planted the seeds of failure in their own strategies for success: the better that business goes for small to midsize spaces, in other words, the harder it is for them to prosper. Staff requirements, travel, booth fees, gallery rent all amount to escalating expenses—but where does the ROI come from? Largely, it doesn’t. I had a meeting with a brilliant gallerist seeking advice (from me?) who has been operating for decades at the highest levels; despite unbridled institutional and commercial support, she is still struggling.

What happens after a gallery nurtures an artist’s career from the larval stages until they spread their wings? They fly away and leave you with nothing. I have the utmost respect and admiration for gallerists—unlike a certain loudmouth private dealer from LA—but it’s an inherently hapless undertaking bordering on a conundrum. Shortly before his death in 2010, Ernst Beyeler, the late Swiss dealer and founder of the namesake foundation, said: “I want to thank those that bought art from me over the years, but moreover I would like to thank those that didn’t, who made me rich.” His point was that you make (some) money selling art, but you create wealth by keeping it.

Frieze

The fact is, people are attracted to art fairs indiscriminately, like flies to poop. It’s a safe bet that the cumulative audience a handful of art fairs draws dwarfs the walk-in traffic of the world’s art galleries combined. Before last week’s Frieze London, I had the feeling that fair had shark-jumped and was on the decline, but I was wrong—I actually enjoyed it more than previous versions (despite the lack of fresh air, making planes seem like spas). It will always have a vital place on the London calendar, but the Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain (aka FIAC, in Paris from October 19 to 22) has certainly robbed Frieze of some of its luster. If I was living in the States I’d choose FIAC instead of making the transatlantic trip twice, as I’m sure many have.

To paraphrase Jonathan Jones of the Guardian: Frieze is hyper-capitalist hothouse, boring and meaningless, pretending to be a museum exhibition. But that misses the point entirely. Yes, we all know the art market is a privileged place for those high up the economic ladder, but meanwhile it’s still free to see art in UK museums and in galleries around the world for those intrepid enough to make the effort. I don’t buy into the accusation that Frieze has any pretense other than to make the selling of art a more layered, varied experience—and they did. Yawn, Jon.

Lisa Spellman of 303 Gallery in New York (who I revere) called this year’s iteration “the happy fair,” as business at her booth was brisk and nonstop busy. It was so busy, in fact, a dealer momentarily lost control of his bladder as a result of the deluge of visitors on opening day and the lack of an opportunity to slip away and relieve himself. That’s the kind of dedication required—stay, piss (in your pants), and play, or go, piss, and pay. Ok, that’s not funny. On the subject of toilets, why they chose to make them unisex this year was lost on me. Unsettling in a very different way, there were (for the first time) cute little dogs roaming the tents and sniffing for explosives. Hardly a cause for peace of mind in our topsy-turvy world: micro-pooches trained to kill (and be killed).

Another observation, not meant in any way to be insensitive: I didn’t see more than a few black art dealers amid the two tents. Yes, artists are flourishing from diverse ethnic, racial and cultural backgrounds, but how many non-white art dealers do you know? I trust this will change, in tandem with the changing fortunes of artists young and old. It’s fascinating to watch: to contextualize the generation of diverse younger artists making their way swiftly to the fore of the art world, the market is searching for past practitioners who have largely been dismissed or fallen through the cracks. Better late than never.

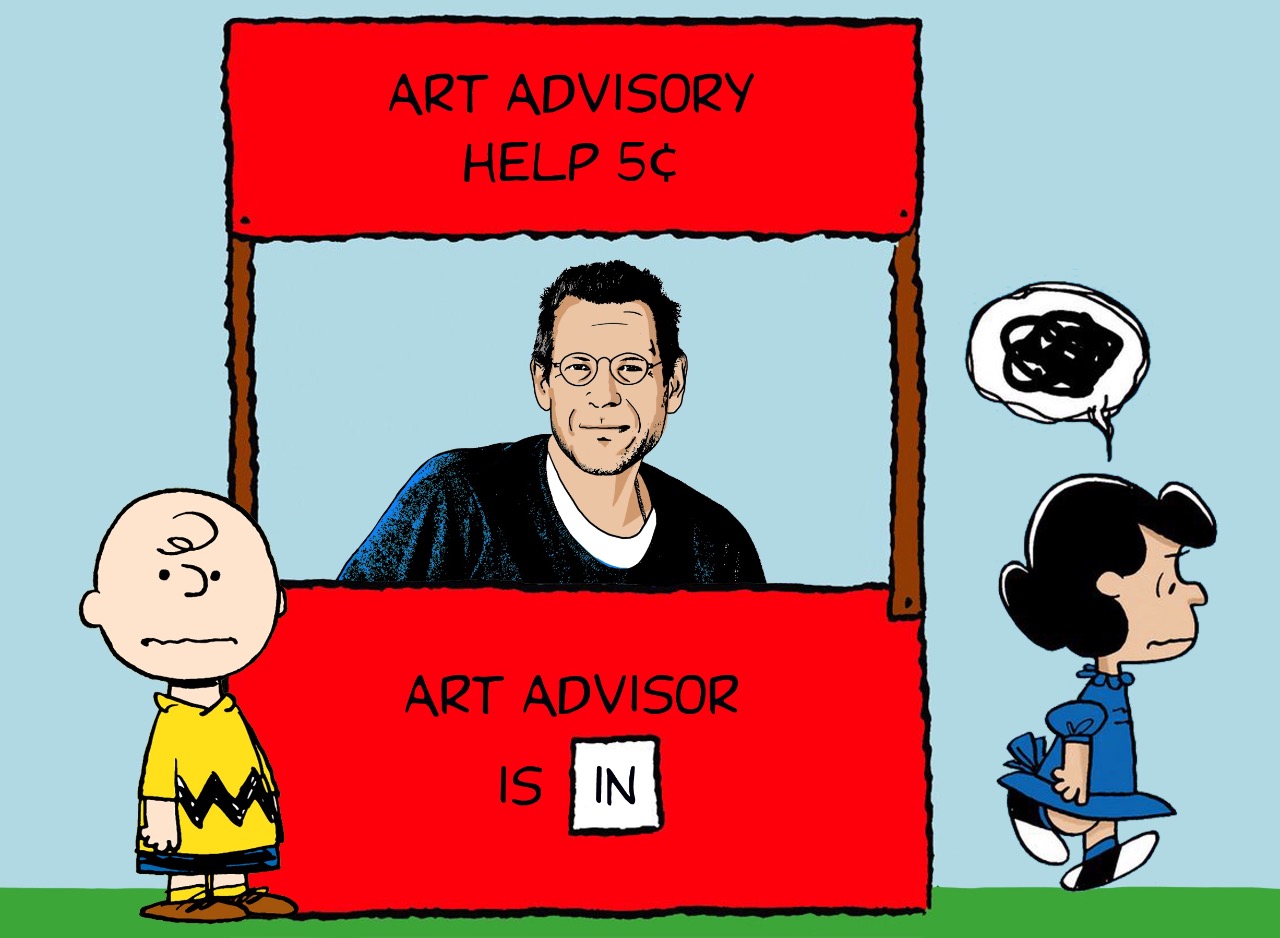

There were probably more art advisors than collectors on hand, but I got the impression that deals were being done at a solid, if not torrid, pace. There’s always a Bell’s Curve delineating the galleries that sell and the ones that simply don’t, with winners and losers in equal measure. Curiously, I received an unsolicited email prior to the onset of festivities from a London advisory firm called Goldhurst asking me if I’d like help navigating the aisles. Clever marketing: the cold email call. But it reminded me of Lucy from Peanuts selling psychiatry services from a lemonade stand. As Charlie Brown would exclaim: “Good grief!” Can someone impose a regulation for art advisors to operate with a license? Even I can do it better than these go-getters (and do).

I’m a big fan of Team Hauser & Wirth—who, incidentally, have a stellar survey of Jack Whitten in London now—and have no intent to disparage their monumental Frieze efforts, but the fake bronze museum concept left me cold. It was more like a colossal distraction, claustrophobically chockablock with art and props. If anything, it brought to mind a bad case of Affluenza (known to be highly contagious) due to the clearly excessive associative costs that, as Jonathan Jones pointed out, smacked of Damien-itis in its superfluous unbelievability and inanity.

The Nahmads started the diorama trend a few years ago to interesting effect, but now it’s devolved into mere show-business artifice. I suggest a moratorium on further such efforts, since they’re a leaky valve detracting from the experience of looking at and buying art. I never understood the meaning of late capitalism; now I just might.

If Hauser can do it, why not me? K-COIN. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The best part, barely noticeable amid the chaos and mishmash of the booth, were coins stamped with an impression of Iwan Wirth, the gallery’s proprietor. I have heard of artists printing their own money, but dealers? Why not? Let it be our turn to make dosh the old-fashioned way, by issuing it. Consider it a kind of art-market Bitcoin. Besides, minting vanity currency is not too dissimilar from schlocky Koons and Hirst merch. I don’t know what Hauser sold on the stand—they always manage to do well—but in the Masters fair (which sounds like a sex fetish) they sold Duchamp’s remade-readymade shovel for $3.6 million. They might have used Marcel’s implement to clean up the bronze museum first.

With Frieze bifurcated into two events, I find it best to tackle Masters on separate days, with fresh eyes, legs, and bladder. You can go to just about any (good) fair every day for six months and still not see everything—not to mention that the booths are constantly shifting as material moves. Blum & Poe presented a one-person display of ginormous Julian Schnabel paintings—most start at XXXL. Whether you like his art or not (no comment), at around $250,000 to $500,000 for the works on view (and less at auction), it represents good value in relationship to the rest of the market, including artists both younger and older.

A painting by Papa Schnabel at Blum & Poe. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Just prior to the onset of the Frieze festivities, I read that Julian’s art dealing son, Vito, was arrested at Burning Man for selling magic mushrooms. (Personally, I’d sooner be shot in the face than attend that ersatz desert neo-bachannal.) Anyway, peddling ‘shrooms at the pleasurefest is akin to selling muffins in a school bake sale. No biggie. But, due to the dealer’s high profile and well documented celebrity love life, it made international headlines—so I made a “Free Vito” t-shirt, all in good fun.

Kenny’s new cause. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Until I got a call from the Master (i.e., his father) demanding in no uncertain terms, and not just once, that I remove the image from my social media. He even had a friend contact me asking how I’d like such a shande to befall my children. Uh, with my infamously errant wild pack of sons it actually does, every couple of months. I didn’t take it down.

Auctions

In China, potential punters are repeatedly admonished by auction houses that bidding at auction is the only trustworthy manner in which to collect. Surprise! But it couldn’t be further from the truth. Incidentally, a tiny Jonas Wood just sold in Hong Kong at Sotheby’s for $463,000; an equivalent-sized painting would have fetched less in New York or London.

Since antitrust laws won’t allow the houses to sit down to an alcohol-fueled meal to coordinate their schedules in unison, Christie’s went at it alone when they nixed their June London auction, as the city is on the decline in a macroeconomic sense. But October will never be a good time for mega-sized sales, either—so it was nothing but foolish for Christie’s to insert a piggishly priced Bacon (£60 million low estimate). That strategy never works, ever, anywhere. Before the auction, Brett Gorvy was working the room like he never left the employ of the company, and he assured me that the London market could rise to the occasion. I like and admire him, but he was proved wrong in this instance.

A client of mine clinched a sale at the fair and a Sotheby’s “expert” talked them out of it; they don’t play cricket (i.e., act forthrightly). One buyer I know was refused an extra seat for the Sotheby’s evening event, even though it ended up sparsely attended and without spark. The sale was more like auctions of yore: trade events for professionals rather than end users. Auctions are tailor-made (read manipulated) to suit one thing: the bottom line.

Just look at the Basquiat that passed in Sotheby’s night sale only to reemerge at auction the following morning so that a late-coming buyer could snag it then—a blatant act of window dressing, pumping up the overall numbers by $5 million and avoiding the dreaded BI. A few years ago, I saw Jose Mugrabi run up to the rostrum at Phillips to recall a lot that had passed because he had been distracted on the phone. It re-crossed the block, and he bought it. (I gather he might have owned it beforehand too—don’t ask.)

Polke’s Mehl in der Wurst (Flour in the Sausage) (1964) sold for £920,750 at Christies. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

In this combined auction cycle, there were a total of 11 Sigmar Polke pieces on offer, which no one seemed to pick up on—a Polke plethora. Though the estate is muddling along with a catalogue raisonné, the Polke market shrugged off that inconvenience and chugged along quite handsomely. Led by Phillips, of all places (you won’t find that occurrence often), six works tallied in the middle of the estimates while five exceeded their highs. When I requested an image of a work from Christie’s, they sent me a jpeg that had been tweaked so much in Photoshop (to make the colors pop) that it was virtually unrecognizable. Of course, I had to write to the specialist and ask why, and he responded, “Sorry we can’t help it.” In addition, Peter Halley, in the midst of a career reassessment, exceeded expectations, while Hurvin Anderson and Grayson Perry smashed them, making huge prices respectively.

Making less economic sense than a small gallery nowadays, Phillips is the perennial underperformer. A recent ex-employee told me that the losses were piling up into the tens of millions, and that it was more burning money than laundering it (his words). Maybe Phillips should torch all the guaranteed leftovers at the next Burning Man; that would be a spectacle worthy of an admision fee, and could go a long way towards boosting the bottom line (for once). They couldn’t even manage to display an Ai Weiwei table correctly prior to the sale, which might cost them a lawsuit from the consignor. The inimitable Phillips style: unrepeatable even if you wanted to (though I couldn’t imagine why you would).

Why won’t people stop telling me stuff? Don’t they know by now? I am like an art-world shrink. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

After a summer of repeated natural disasters—and, worse, the manmade variety (it’s never women that shoot)—the fall is off to a rollicking start despite continued bumpiness in the UK. I foresee good tidings ahead from my own selfish perspective. During Frieze, I tried to exercise self-restraint and refrain from buying anything, but I failed (as I am wont to do). With Oscar Murillo’s Polke pastiches selling for $400,000 at Zwirner, the Katharina Grosse at Johann Koenig seemed like a steal at a fraction of the price.

Kenny’s new Katharina Grosse. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

As the art world continues to rapidly transform, Art Basel is poised to monopolize the miles-of-aisles format, becoming the Gagosian of fairdom. Opening regional events in Dusseldorf (and elsewhere) is a zero-sum attack on indigenous fairs like Cologne, where I started my career and remain loyally partial to. I hear they have their sights set on many more sites to come, including possibly Shanghai, where there are two concurrent fairs, West Bund and 021. I will present a project in November at 021, though I haven’t had a gallery space of my own forever (certainly not a professionally run variant). That makes me think: I should start a fair for dealers with no galleries.

The art market is like Dostoyevsky: there’s no shortage of crime and punishment, but I’m left with nothing but a rictus grin and an appetite for more. Bring on FIAC, Shanghai, Miami… and beyond!