On the road in Sicily in a 1970 Fiat Abarth Rally car. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

After Damien Hirst’s undersea extravaganza in Venice left me feeling like a splashed-on tourist at SeaWorld (albeit one with much nicer aquariums, and a different kind of whales), I dried myself off and headed to the more arid and level-headed climes of Brussels to see some galleries and take in the Independent art fair.

Space in Brussels is so inexpensive in relation to other European and US cities that perhaps Damien’s “Unbelievable Wreck” could find a permanent home there. Clearing, for instance, opened a vast new gallery (they have another in Brooklyn) with an exhibition of Bruno Gironcoli (1936-2010), an obscure Austrian artist who trained as a goldsmith and even has a museum of his very own located in a castle, Schloss Herberstein. The works in the show would give Hirst a run for his money in scale. They are wacky, large, and a little incomprehensible, but I’m a huge fan of the gallery and their program, including Harold Ancart, who premiered a new painting show with Xavier Hufkens that also opened in town during the fair.

Harold Ancart (detail) at Xavier Hufkens. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The second edition of Independent Brussels took place in a large, airy, city-owned building. (There have been seven editions in New York, where the fair originates.). Elizabeth Dee, the founder, said she was not on the ground to compete with Art Brussels, the longstanding game in town, but rather for the love of the city. Okay. There were five sparsely-populated floors of exhibitors (more than 60) and many of the booths had four walls instead of the norm, a rather restrictive three.

Local collector Alain Servais spoke in these pages of the need for the opposing fairs to join forces and unite, arguing that there is no room for dissension in such a small city. Funny, because the collector, a self-appointed big fish (but in a very small bowl), is often seen attacking his peers (like me) on his rambling Twitter account, and told me at an opening that I was the Michael Jackson of the art world—before correcting that to Woody Allen. Perhaps they should call in Jean-Claude Van Damme to use his muscles in Brussels to settle the score of the simmering battle of the fairs (and take care of a certain righteous collector while he’s at it). The stakes of these regional fair fights, however, are no joke: the MCH group, which controls the Basels, has ratcheted up the drama by opposing Art Cologne with a newly announced competing event in Düsseldorf slated to debut this November. Fallout there will surely be, so stay tuned.

Meanwhile, back in Belgium, David Zwirner (not himself on hand for the festivities) participated in Independent Brussels for the second year in a row, as the gallery prefers the “more casual spirit.” When I queried after some prices, a sales assistant said, “I’m not allowed to tell you! I got in trouble last time.” “Me too,” chimed in another. But I persevered on various gallery prices and uncovered a $95,000 Jordan Wolfson computer print, a $15,000 Marilyn Minter photo, and a fabulous Rose Wylie painting for $60,000.

Rose Wylie at David Zwirner. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Distinctly non-Zombie Formalist Walter Robinson’s paintings were on view at Stems Gallery of Luxembourg and Brussels for between $4,200 to $32,000. Panamarenko (b. 1940), the reclusive Belgian sculptor of dirigibles and other flying and driving machines, had works at Mulier Mulier Gallery of Knokke, the Belgian St. Tropez. The artist quit making work some years ago because, according to the gallery, he said, “My story is told.” I wish more artists took note of the sentiment.

I didn’t have time for Art Brussels—you need to choose your priorities—and instead flew to Palermo, the capital of Sicily, for the running of the Targa Florio, the world’s oldest sports-car racing event that takes place on open public roads. To hell with health and safety!

I actually participated in Art Brussels in 2005, and installed a museum-quality stand with the likes of Robert Smithson (the work formerly belonged to Eva Hesse), Richard Tuttle, Paul Thek, and the now-departed Vito Acconci (about whom I will have more to say soon). I managed not to sell a single piece. But that’s not the only reason I skipped the fair. I was also trying to avoid the syndrome that art advisor Lisa Schiff recently described in the New York Times as the “numbing saturation” brought on by the surfeit of art fairs. I am not sure that’s an affliction you fancy your consultant to come down with.

Start of the Targo Florio race in Palermo, Italy. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

As for the historic race, Fiat generously invited me to participate in the classic category due to the fact I have a 1970 124 Abarth rally car. I will display a group of old cars (and some Zaha Hadid models) at the main section of this year’s Design Miami/Basel in an exhibit called “#MANUAL.” A manual is non-autonomous car you actually have to drive yourself (as opposed to stick shifts, which are all but extinct). Maybe artnet can take a page from Fiat and embrace the notion of an all-expenses-paid junket (for yours truly).

In Palermo, I was paired in my car with co-driver Mark Dixon, a Cambridge-educated journalist from Octane magazine. I pitied the fool stuck with such a lousy driver, i.e. me. (I love the designs more than I have the time and inclination to get behind the wheel.) From the get-go, I faced the dilemma of whether to tell him how faulty my brakes were. But before I could fail the test, he figured it out for himself.

Kenny in his 1970 124 Abarth rally car. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Driving a classic car reminds me of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, in which an American farming family drives across the country seeking work during the Great Depression. They are dependent on the reliability of their truck, literally, for life or death. Every sound and smell emitted by the vehicle takes on a hyper sense of urgency for the despondent family.

Not to be (too) superficial, but driving my Fiat up and down the mountains of Sicily was not too dissimilar: my eyes were glued to the malfunctioning oil-pressure gauge, which, if I had been reading it correctly, would have indicated the engine might seize, or worse. Mark and I are both around the same age and began comparing which capsules we start the day with; maybe I should replace the oil-pressure gauge in the dash with a blood-pressure monitor. I’m considering gifting Mark a Hirst pill print for having to suffer me while risking his life and limbs. Or maybe even one of Jeff Koons’s ridiculous new designer bags for Louis Vuitton, if I could sneak past the lines of brand-gullible women (and men) queuing up to buy them.

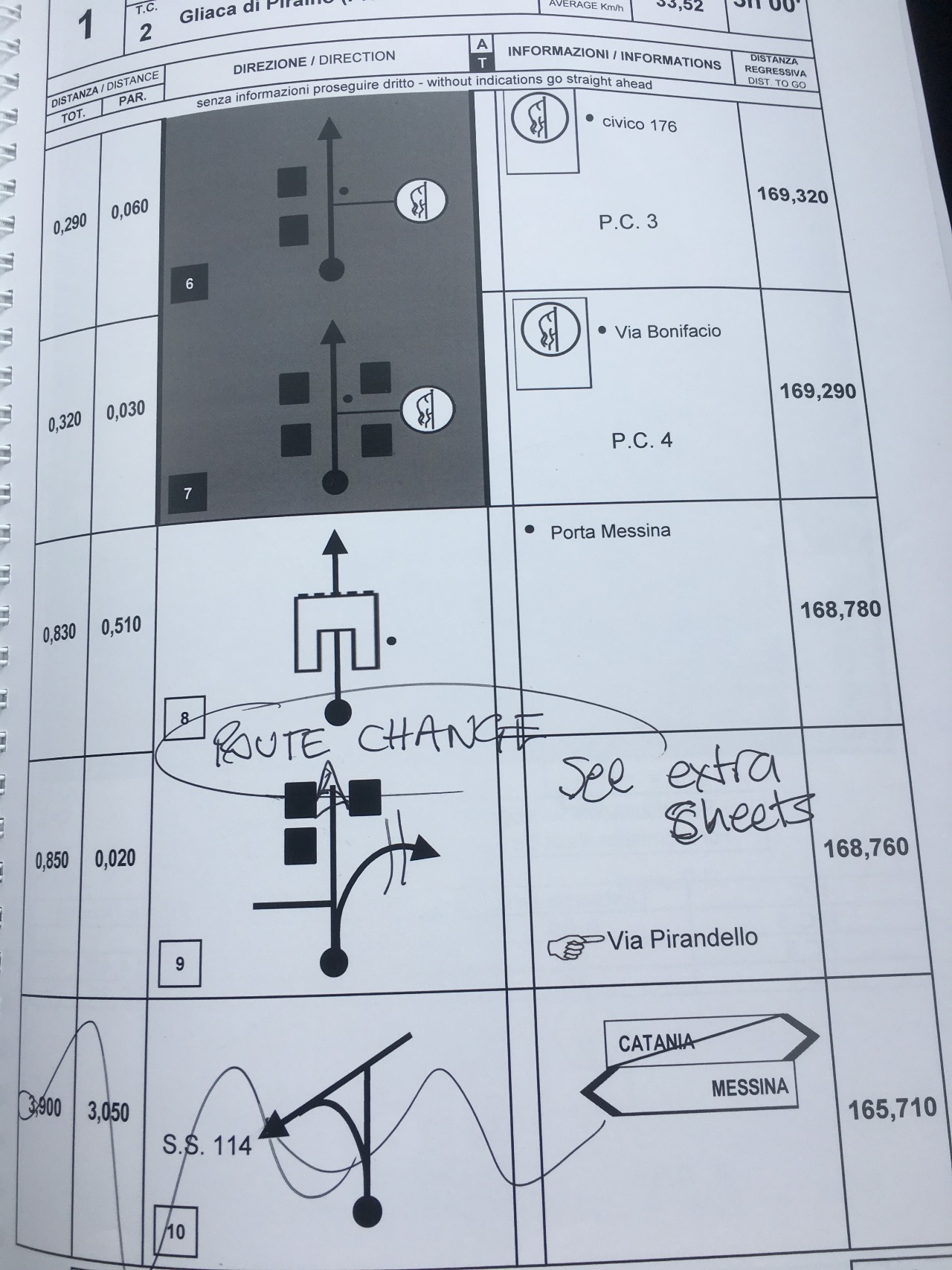

On one occasion, I even struggled to drive close enough to a toll booth and nearly fell out of window stretching for the ticket. But I have an inherently flawed sense of direction, and reading the indecipherable pace notes mapping out our route was not an option, so I was the designated driver throughout. After re-fueling, Mark returned with an open coffee and a powdered-sugar croissant; the crumbs went in one direction, the sugar in another, and the coffee, largely on his lap. The Woody Allen in me nearly had a heart attack.

I had spent much of the trip trying to negotiate a Rudolf Stingel deal, but now on the road, was helpless to answer the phone, which rang until the battery died. The laissez-faire local policemen didn’t blink an eye when we speeded by—they even joined the tour. There was a sense of camaraderie on display with men and women of all stripes and from disparate socio-economic backgrounds, though the racial mix was about the same as any given Basel: pretty homogenous.

The pace notes for the race. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The sensation of driving on pedestrian walkways through centuries-old towns was utterly indescribable. Wending up and down the hairpin curves of the mountains and along the coast, I often had to restrain myself from sightseeing for the well-being of my co-pilot. The (active) volcano, Mount Etna, was in sight for much of the drive.

It was beautiful… and exhausting. After the first day of the race and dinner, depleted, I stepped out on my hotel balcony to admire the sea view and got locked out—in my boxers. On the fifth floor between the street and Mediterranean, I began to yell for help. An Italian couple on the sidewalk responded and asked which room number I was before the neighbor popped his head out on the adjoining terrace and offered to assist. Ten minutes later, with no help in sight, I began to yell again at which point the fellow driver from next door reappeared and said I’d given him the wrong room number (I’d been in a handful in as many days) and relief was imminent. Except it wasn’t. Panicking, I pleaded, ever more desperately, before an Italian from a few floors below stepped out but didn’t speak a single word of English. Forty-five minutes elapsed before I was able to force the door open. No one ever came to rescue me. It was a Kafkaesque experience that made the driving seem easy.

On the road, my overwhelming cowardice quickly faded once I got going and found a rhythm—it’s a very physical act to control a car at speed for extended periods. Sweaty palms were the order of the day throughout, and if god forbid I didn’t get the directions right (more than once), Mr. Dixon felt no compunction yelling at me; I felt right at home. If I had been driving with a friend, I’d probably have killed myself from recklessness. Tragically, on another section of the race, there were two deaths. I thought the art world was dangerous. Numbing sensations or not, I’ll stick to art, thank you very much.

Video courtesy of Kenny Schachter.