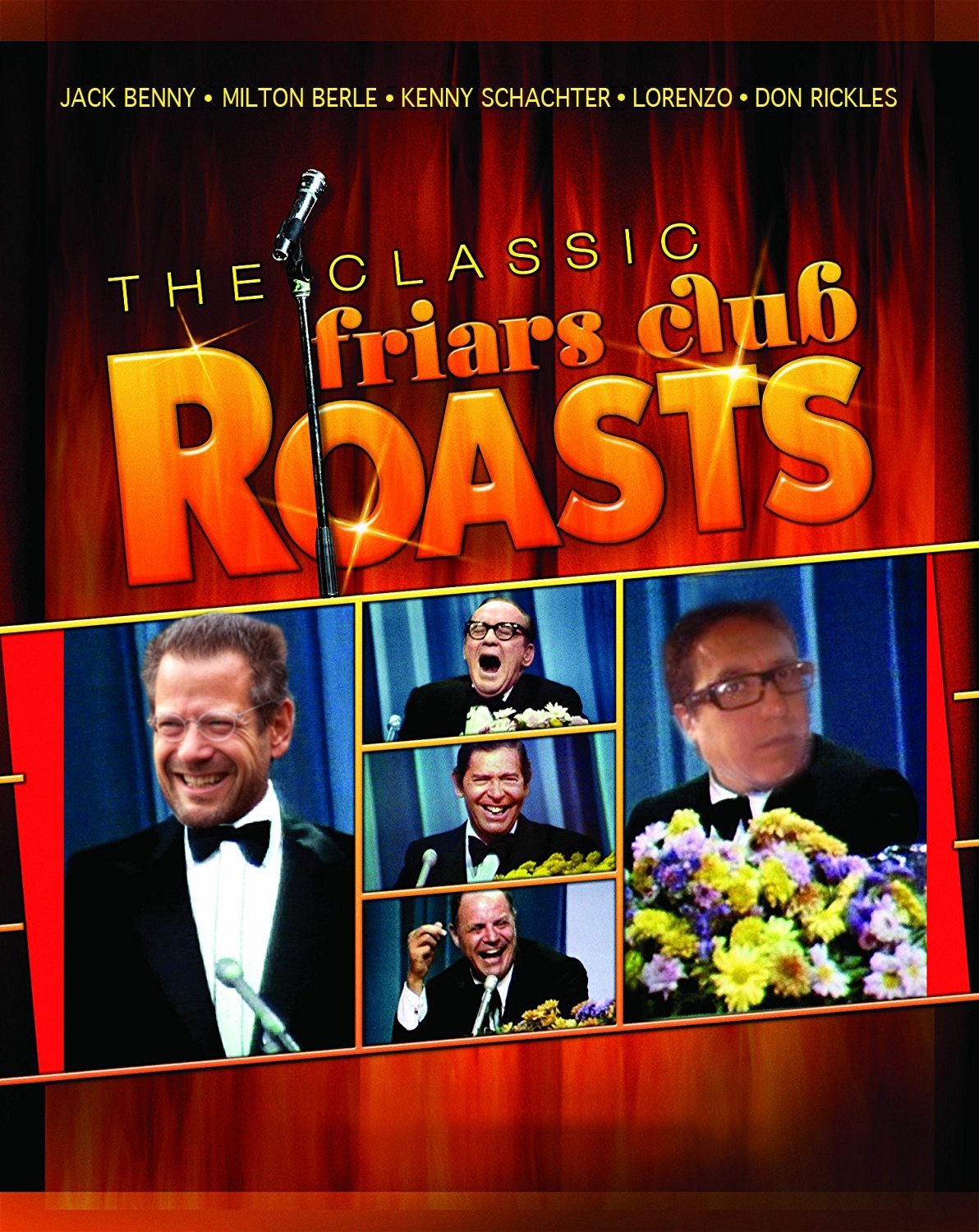

Image courtesy Kenny Schachter

Roving the art world for business and pleasure, I was en route to New York for the Armory Show and its attendant fairs and goings-on when I had a near miss with a sneering Tracey Emin, and struck a possible deal with Harry Blain of Blain|Southern Gallery. This was before I had even left the tarmac at Heathrow. Besides market clatter (which I never tire of, really) my plane neighbors were so loud I resorted to Pzizz, a meditation app originating from a group of university linguists in California (where else?) that sends you into that twilight between asleep and awake with an array of soothing sounds and mildly annoying positive cogitations. In the mercenary market, it’s an inestimable tool. I implore you to try it! While Pzizzing, I couldn’t get it out of my head that Harry had managed an insane package deal with British Airways and the Carlyle Hotel (aka art-dealing central) at a total cost less than one leg of my airfare. My tranquility was blown before I landed.

Photo illustration courtesy Kenny Schachter

The Armory Show (the contemporary iteration) launched in 1994, and I participated in it from the mid-1990s—when it was a shabby, down-to-earth undertaking in the Gramercy Park Hotel—’til I was thrown out 20 years later due to my secondary-market offerings, breaching a then-tenet of the fair not to include historical fare. (This was before they opened it up to the older stuff, hidden atop a winding fight of stairs in Pier 92.) I wasn’t being impertinent, I just had never read the small print—which is ironic considering I spent two eight-hour days taking the bar exam in 1987 on the very pier where the fair resides today. I think fondly of the hotel version, when the Armory unfolded in the guest rooms with beds upturned to maximize space and art installed willy-nilly everywhere except on the walls, which was the only verboten act in the anything-goes fair. It was all about the art and artists. Those were the days.

Of course, back then (nearly a quarter-century ago) the art-market waters were shallower, with fewer fishes. Things were simpler, too, with only a single New York contemporary fair (its American forerunner being EXPO Chicago, begun in 1980) and little new art being bought and sold at auction, the profit center now. On occasion of the 23rd iteration of the Armory, there were seemingly millions of fairs running concurrently (featuring loads of artists) and actual millions of dollars at stake. After rummaging through each of these fairs, I think I’ve lost all feeling in my art-appreciating organ (if I ever had any to begin with).

The Armory Show

A former editor of mine at artnet News, Ben Genocchio, took over the reins of the Armory last year with the hope—and mandate—to inject some much-needed pizazz (not the app) into the waterfront behemoth. But distinguishing between these melancholy (af)fairs is no easy feat. Besides, I’m not too sure anyone really wants or expects much in the way of change—in which case, they wouldn’t have been disappointed. The aisles could be as airless as during the grueling law boards—you must be intrepid and energized to make the most of the slog. I admire Ben, his rhetorical flourishes and sartorial style, evidenced by the wild suit he rocked at the opening. But besides his showmanship (read on), can the wheel be reinvented? Does management have an appetite for novelty beyond tweaking the status quo? Moving a couple of contemporary galleries to the Modern section, adding a curated section and a veritable Kusama park doesn’t quite amount to an insurrection. But this event is about selling art, and many did. A booth at the Armory Show will set you back on average $50,000.

As soon as I entered, Jerry Saltz buttonholed me to have my picture taken in an impromptu mini studio for a New York Magazine article and asked me a question about the differences between the U.S. and U.K. art worlds before he became distracted and walked off mid-sentence. I understand: he can’t move a meter without being accosted by fans of every stripe, all from reinventing a critical model. Hats off. He did make a righteous comment about alcohol intake that grated, but he’s never sold a work of art or socialized in the pursuit thereof, so how could he understand?

Viewing Brian Belott’s latest puff wall reliefs at Los Angeles-based Moran Bondaroff—or Puuuuuuuuuuffs, as the artist refers to them—I mentioned to the gallerist that I gave Brian his first show, What’s Going On, in New York in 2004. He responded that I’d told him four times already. Make that five. I’m old and the art world is like the film Groundhog Day, where every day is an endless time loop (or fair, in this case). London’s Pippy Houldsworth Gallery works with the collaborative Bruce High Quality Foundation, which during the heyday of Zombie Formalism sold for a record $425,000 at a Sotheby’s New York November evening sale (!) in 2013, but the market winds have blown. Myself and another collector in the booth both did a double take when we simultaneously misheard $8,000 for $80,000 as the going rate for a primary painting. Things have been set back, but not that much. For them anyway.

Bruce High Quality Foundation at the Armory Show (Courtesy Kenny Schachter)

Carolina Nitsch of New York, who specializes in editions, had a pair of Ai Weiwei Qing Dynasty wooden chairs dating from 1644-1911, from an installation at dOCUMENTA entitled Fairytale–1001 Chairs, going for $45,000. Her wall label conveniently left out the number of chairs extant, which is plenty, even by the standards of Weiwei who (notoriously) never saw a ceramic vase he didn’t feel the urge to paint a Coke logo on. Pace was trying to exhibit a work by Studio Drift consisting of a concrete monolith 4x2x2 meters that was meant to float though space on a controlled three-dimensional path. It didn’t while I hung around. The extreme heat on Pier 94 caused the helium inside the faux-concrete balloon to expand, and the suspended object had to be beached before it exploded (which I might have paid to see). Any art that needs to be turned on is bound to turn off—at the most inopportune instant no doubt. That’s why I’m a painting (and drawing) prude.

Larry G. and Hauser & Wirth were noticeably absent—I guess they didn’t get in. In seriousness, things are better once in a while without them—though you miss their consistently infectious, hyper-buzzing energy, you could even consider the Armory Show a palate cleanser thanks to the absence of the big guns.

The Sarasota Museum of Art

I was asked to speak to trustees of the Sarasota Museum of Art (set to open in late 2018/early 2019 as part of the Ringling College of Art and Design) by longtime friend and museum director Ann-Marie Russell, who helped in the accreditation process of Christie’s education program back in the 1990s, and whom I lectured for then. The first thing that occurred after consenting was that I need to learn how to say no. But, I’ll admit, it was a welcome break in the middle of the New York proceedings to be wading in the Gulf of Mexico. The sea is rife with wildlife and I nearly stepped on an ominous-looking washed-up spiked pufferfish said to be more poisonous than cyanide, enough to kill 30 adults from a single squishy offender. The toxicity reminded me of the antics I left behind in New York.

A puffer fish in Sarasota. Courtesy Kenny Schachter.

The school and formidable John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art—with a room of floor-to-ceiling Peter Paul Rubens and plenty of other masterworks—was left to the state by Ringling as his circus empire was crumbling and bankruptcy loomed. (It was a handy time to be struck by the altruistic impulse and gift his house, galleries, and collection—before his creditors fed on the stash like vultures.) It was all to our benefit to this day, I’m delighted to report, and I highly recommend a visit for many reasons, including the city’s very own school of mid-century architecture led by Paul Rudolph (1918-1997) and his disciples. Every person I met was incredibly nice—and what’s scarier, meant it. During my talk, when I flippantly called a Boston surgeon who embezzled money from a children’s heart fund to forge an ahead-of-its-time collection “astute,” there were audible gasps. One guest weighed in at 102 years of age, and another was a museum intern at 82. A few asides on Sarasota: there’s no income tax there, the Ringling Bros. circus folded after 146 years in January, and the international contemporary art market has become a talking point, even for the uninitiated.

Spring/Break Art Show

The Spring/Break Art show is in its third year, founded by artists Andrew Gori and Ambre Kelly in 2009 to “challenge the traditional cultural landscape of the art market” by selling art in another fair format, apparently. But it’s the best, most vibrant of the lot, despite the challenge of sifting through such a mishmash of quality and presentations. The “booths” are free in exchange for 30 percent of the take, and the art is sold through an ecommerce site that consigns the works through April, so they don’t have to rely on the honor system. Alternatively, dealers can pony up $4,000 if you are certain you will kill it sales-wise and don’t want to share too much of your bonanza. Spring/Break offers art that’s unmoored to the familiar and is frankly an effort to look at. But there was an exuberant level of good intentions, and lots to see if you looked hard enough.

Outside there was a line in the frigid, bone-numbing cold, brrr, and inside there was a theme (of all things). This year’s was black mirror (before that, copy and paste). I don’t think any attendee, if they hadn’t been informed, would guess there was an intended connecting thread. Maybe this will clear it up for you from the release:

“…black mirrors in the physical include our out-of-pocket looking glass, an Apple® a day, that Narcissus pond of 1’s and 0’s. Sext acts are a Voodoo doll of signifier/signified, our avatars bordering on occult, a world we wish into our devices a kind of crystal ball.”

I’ll leave it at that. But what I did discern was that (allegedly) political art incorporating flags—shall we call it “flag art” or “flagism”?) is the new Zombie in the house. The uncontested 1988 & ’89 winner of Spy Magazine’s Iron Man Night Life Decathlon, intrepid 80-year old writer and cartoonist Anthony Haden-Guest, was hard at work in a booth drawing away. From party warhorse to cartoons for coin, maybe I should have asked him to repay the loan I gave him about 20-odd years ago.

Anthony Haden-Guest. Courtesy Kenny Schachter.

Rounding another corner, of which there is a plethora in the unorthodox Times Square building, I twisted my head like a confused dog when I encountered What Does It All Mean? Flippers, Markets, Deals, a piece by fair co-founder Ambre Kelly that included portraits of each individual listed in one of my previous articles: “Killed Deals, Crashing Markets, Flailing Flippers: What Does It All Mean?” published in 2015. There were clumsy canvas renderings (purposeful one assumes) of the likes of me and Leo (DiCaprio) attached to a larger canvas hand painted with the text of my article. Ambre wouldn’t reply to my request for meaning but I suspect—as the fair’s theme was the evasion of navel gazing, and she was an organizer so probably adhered to it—that her piece was about the Post Narcissistic Ego Exercise (a Paul Thek drawing title) that is the art market. Funny. Spring/Break is a naïve, artist-driven initiative, which is a refreshing alternative to the typical money-go-round that rules art—discourse and content alike.