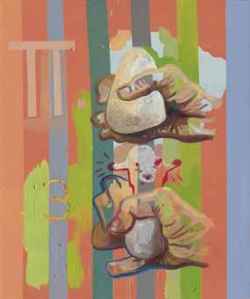

An untitled Kippenberger from 1996 that sold for about $703,000 at Christie’s. (Courtesy Christie’s)

Kenny Schachter is a London-based art dealer, curator and writer. His writing has appeared in books on architect Zaha Hadid and artists Vito Acconci and Paul Thek, and he is a contributor to the British edition of GQ. The opinions expressed here are his own.

>You won’t find Leonardo DiCaprio at an auction house’s day sale. By stark contrast with the glamorous biannual evening sales of contemporary art at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips, those houses’ corresponding day sales, where artworks of lower value are sold—often recently-made artworks by young artists—are much more somber, matter-of-fact events. You may spot the nephew of the shipping magnate, but are unlikely to see the magnate himself.

Younger specialists man the phone banks—the day sales are finishing schools for art dealers, specialists and collectors alike—and even the acoustics are different. As opposed to the dramatic hush of the salesroom during the evening sales, the room is alive with chattering, sometimes so loud that you can barely make out the auctioneer’s words. The standing-room real estate at the sides of the aisles, which during the evening sales is chock-a-block with journalists, is barren.

The day sales run at a different pace. At the evening sales, the audience, many of them formally attired, tends to show up before the action begins. Not so during the day. By the 1 p.m. starting time at Christie’s on Friday, only a smattering of private dealers and a handful of collectors had turned up. And once things start, you can feel the steady hum of the market at work. A common sight is an individual swooping down on the winning bidder, passing along a business card and mentioning they have access to five more of the same.

The day sales are largely professionally driven, generally peppered with an array of art dealers, there to buy inventory, and to protect their artists’ markets. In London, that means some of the industry’s greatest professionals like Sadie Coles, Per Skarstedt and Thomas Dane, or their staffers. At Christie’s, Bona Monagu of Skarstedt nabbed a snappy untitled painting by Martin Kippenberger for £422,500 ($703,000) on an estimate of £200,000–£300,000 ($332,000–$498,000).

What the day sales lack in sexiness, they make up for in information. They can be fascinating forums in which to observe developments in the market beyond the hoopla and headline-grabbing Mega Millions achieved in the evening events.

Before February’s round of contemporary sales started in London last week, some market watchers thought there might be a correction, even if a mild one. That didn’t happen. The contemporary art market, across the board, is in rude health.

Testifying to the greater presence of speculators in the market is the fact that artworks are being churned through the system with a new swiftness. You see pieces, some of them made just a few years ago, resurface that were sold at other day sales just six months ago. It’s a pattern that echoes what has been happening on the international art fair circuit, with artworks selling at one fair, and selling at another, sometimes within a year.

The sales also spoke to a market that is in flux. Another factor in art selling’s more rapid pace is the fact that sales are increasingly made via social-medias sites like Instagram and Facebook. New channels and networks of participation have been established.

And those new channels and networks seem to be mostly facilitating the sale of work by young male artists. I will try to avoid reiterating the public maelstrom over a group of young, mostly white men making repetitive, seemingly shallow and thoughtless works, in big series—and making bigger and bigger prices. These works have a tendency to be bought, sold and re-sold while the (spray) paint is still barely dry.

‘Untitled (Burrito)’ (2011) by Murillo, which sold at Christie’s for about $323,000. (Courtesy Christie’s)

I have a hunch that every work the Columbian-born, 25-year-old artist Oscar Murillo has ever made—and he’s made quite a few—has changed hands at least once. Or will do so shortly. Despite this, they continue to pull in solid numbers, the highest this go-round was a 2011 painting that made £194,500 ($323,000) at Christie’s evening sale on Thursday.

Last week saw the auction debut of Eddie Peake, the 32-year-old son of artist Phyllida Barlow. Mr. Peake has just sold out his first solo exhibition with Javier Peres gallery in Berlin. At Christie’s day sale, his 2013 artwork Syc Aro Tin—lacquered spray paint on polished stainless steel—sold for £32,500 ($54,000), more than double its £15,000 ($25,000) high estimate.

Bidders in the room included Hugh Gibson, who purchased a small Richter for £314,500 ($524,000) and the son of noted dealer Thomas Gibson. Another was professional collector-dealer Carl Kostyál who recently opened a space in Stockholm, Sweden. The Peake eventually sold to someone bidding anonymously over the phone.

It shouldn’t be long before loads of Peakes come out of the woodwork and into the marketplace; that’s the way it usually goes.

‘F (A thing is a thing in a whole which it’s not)’ (2012) by Ostrowski, which made about $145,000 at Phillips. (Courtesy Phillips)

Not unlike all the auctions last week, Phillips’ day sale on Tuesday was predominantly a male sale. The eyebrow-raising result was the £86,500 ($145,000) achieved for the 2012 painting F (A thing is a thing in a whole which it’s not), by young Cologne-based artist David Ostrowski. This was Mr. Ostrowski’s auction debut, and the piece’s high pre-sale estimate was just £15,000 ($25,000). Stay tuned—his market is likely to combust.

Then there is Lucien Smith, who at the ripe age of 25 has already experienced 12 re-resales of just-out-of-the-studio works ranging from paint squirted “rain” paintings to pigment-encrusted pie tins adhered to canvases. He seems to be making a lot of work—there are plenty of pieces available from each series—and that’s always a factor in a burgeoning market.

A big blue rain piece of his went at Phillips for £194,500 ($325,000) at the evening sale against a high estimate of only £60,000 ($100,000), but a nearly identical work in the same color only made £158,500 ($263,000) at Christies a few days later. Could this be the beginning of a Lucien Smith market setback, or backlash, to the tune of nearly 20 percent?

But there were six works in all by Mr. Smith in the day sales, and overall he held his market position, and continued to make remarkably strong prices. His small (24-by-18-inch) rain works, dated 2011–12, hit £47,500 ($79,000) at Phillips and £48,750 ($81,000) at Sotheby’s. Unsurprisingly, there’s already a handful more pieces slated for the upcoming midterm New York sales in March coinciding with the Armory Show; look for the momentum to stay strong, for the time being at least.

(Incidentally, Mr. Smith’s pie tins from 2012-13—does he intend them as pies in our collective face?—went for £15,000 ($25,000) at Phillips and £30,000 ($50,000) at Sotheby’s, which would tend to confirm my long held maxim: better to sell at Christies and Sotheby’s and buy at Phillips, which is still (and will probably always be) the junior market maker.)

Another much-discussed result at the day sales was the £56,250 ($94,000) paid at Sotheby’s for The Agony and the Ecstasy, a 2012 artwork by auction first-timer Parker Ito (b. 1986). The piece was estimated at only £15,000 ($25,000).

Side view of ‘The Agony and the Ecstacy (2012) by Ito,’ which sold for $94,000 at Sotheby’s. (Courtesy Sotheby’s)

A Los Angeles-based artist, and one whose work is entirely new to the auction block, Mr. Ito is the poster boy for what’s become known as Post-Internet art, a concept or marketing slogan I admittedly don’t understand, but I confess to liking the way some of it looks. To my eye, it’s not even post-painting. The price was a little wacky but, if lit just so, the piece does manage to sing; I’m just not sure if Mr. Ito will turn out to be a one-hit wonder. (As for Post-Internet, given the number of Internet bids in today’s sales, we may well be in the post-art-dealing era, or at least post art dealing as we knew it.) Lastly, the piece is made from vinyl over enamel on 3M Scotchlite. I may be wrong but the agony might belong to the buyer when this thing ultimately disintegrates and/or becomes worthless, in which case the ecstasy will be strictly the seller’s.

Results for midcareer artists were uneven. The mid-career artist Anselm Reyle (b. 1970) recently announced, in an interview in a German newspaper, that he is retiring from art making. His studio had gotten away from him creatively and financially, he said, and he made the determination to retire from art altogether rather than run his enterprise at a loss.

And judging by his results last week, he might have been right to do so. Yes, his signature boxed colored aluminum foil work doubled its high estimate to make £80,500 ($135,000) at Phillips, but that’s a far cry from his 2007 auction record of $634,052, for a different foil work. With two artworks failing to sell at Phillips and Sotheby’s, respectively, Sam Taylor-Wood-Johnson (her latest husband Aaron, born 1990, is younger than Lucien Smith) might consider following suit.

‘Is Legal Sex Anal?’ (1998) by Emin, which made $124,000 at Christie’s. (Courtesy Christie’s)

But good old YBA Tracey Emin (b. 1963) more than made her numbers at Christies with a lovely pair of gems in neon: “Is Legal Sex Anal?” sold for £74,500 ($124,000), over an estimate of £12,000–£18,000 ($20,000–$30,000). “Is Anal Sex Legal?” fetched £62,500 against an estimate of £12,000–£18,000 ($20,000–$30,000). The flummoxed auctioneer stumbled over the titles, stating, “That’s a good question,” and “That’s also a good question.”

Last week, Damien Hirst’s work ran the gamut, at Sotheby’s and Phillips, from not selling, to selling low, to selling high. I’d attribute this unevenness to the lack of clarity as to whether the market has welcomed him back and forgiven him for selling seemingly thousands of works in one go at Sotheby’s in 2008 for hundreds of millions, just as Lehman Brothers crashed.

Mr. Hirst’s Clamy Love, an orange oval with scattered embedded butterflies failed to sell at the day sale at Sotheby’s; it carried a presale estimate of only £200,000-£300,000 ($334,000–$501,000). Orange is not red, the market darling of colors. But a small 1997 medicine cabinet entitled Shh blew past the high estimate of £100,000 ($167,000) to sell for £176,000 ($294,000), also at Sotheby’s. Mr. Hirst’s market remains healthy, generally speaking, but it’s very selective.

Looking cheap compared to some of his contemporaries like Christopher Wool (b. 1955), a small yellow joke painting by Richard Prince (b. 1949) fetched the princely sum of £242,500 ($405,000) at Sotheby’s against a high estimate of £120,000 ($201,000). Two other photographic works by Mr. Prince also doubled, or nearly doubled, their high estimates. Now that a judge has green-lighted Mr. Prince’s continued license to copyright infringe, his auction market may be experiencing a comeback, though five paintings from the “Canal Zone” series are still in legal limbo, awaiting adjudication to determine if they in fact crossed some moral line.

The Chinese artist Ai Weiwei (b. 1957) got stand-up prices from a series of sit-down sculptures, all of which were only recently available in editions, or still are. And for much less! But that’s the auctions and the sometimes-less-than-well-informed fans they attract.

‘Fairytale’ (2007) by Ai made $84,000 at Christie’s. (Courtesy Christie’s)

A tricky game in Ai Weiwei’s market is gauging the precise number of iterations of each series he makes, frequently in unnamed and unnumbered editions. This is not the case with “Fairytale,” a series of 1,000 chairs gathered for 2007’s Documenta exhibit in Kassel, Germany. A pair went for $37,500 last May at Sotheby’s and last week for £50,000 ($84,000) at Christie’s, not a bad return in less than a year for a huge edition of readymades.

The same held true for a Serpentine Gallery stool from 2012, initially marketed as a collaboration between Mr. Ai and architects Herzog & de Meuron in an edition of 20 for £6,500 ($11,000) each. Last week, it was presented for resale at Phillips in the sexier guise of a solo work by Mr. Ai, and it made £13,750 ($23,000). Rocks, also sit-able but in an unknown or stated edition, made £68,500 ($115,000) against a high estimate of £40,000 ($67,000). Mr. Ai’s market is clearly back after some stalling.

As for older art in the day sales, I have been in an ongoing argument with my next-door neighbor, who reasoned that the 2010 auction record of $887,084 for Op artist Victor Vasarely (1906–97) was every bit as good as the $5.1 million record for Bridget Riley (b. 1931), achieved in 2008. My neighbor saw no reason why top art dealers wouldn’t be jumping in on the Op Art bandwagon soon, and bought what amounted to a trading position in the work. Turns out he might be on to something. Though they remained under $100,000, four early artworks by Vasarely smashed through their high estimates at Sotheby’s. All the same, Vasarely is still an Op-Art bet I’d opt out of.

My feeling is that for the foreseeable future the art market will continue to expand—and then some—before there is any kind of correction. The May sales in New York (the next spate of major actions) will likely be explosive.

The grand totals for the day sales (including buyer’s premiums) amounted to £13.4 million ($22.4 million) for Christies, £16.6 million ($27.7 million) for Sotheby’s and £4.6 million ($7.6 million) for Phillips—no single figure much more than what a single meaty abstract painting by Gerhard Richter would bring at an evening sale. But the snapshot they present of where we are at a given point in time in the contemporary art market is priceless.