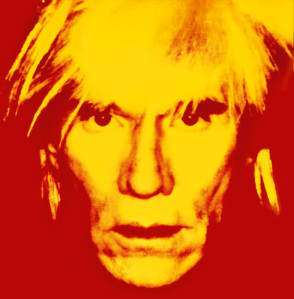

Andy Warhol’s eye-popping 1986 self-portrait, at Caratsch.

Kenny Schachter is a London-based art dealer, curator and writer. His writing has appeared in books on architect Zaha Hadid and artists Vito Acconci and Paul Thek, and he is a contributor to the British edition of GQ. The opinions expressed here are his own.

I’ve always been a hesitant skier, even before the Sonny Bono and Michael Kennedy mountain misfortunes. This week, I turned my back on the slopes for an hour and a half, gathered together a group of enthusiastic New York friends, and made the rounds of St. Moritz’s handful of galleries, all of them within walking distance of each other.

We strode cautiously through the snow to the ambitious new gallery of Zurich dealer Andrea Caratsch, his second in town—it’s a bold move in light of the seasonal character of St. Moritz and scale of the space. It’s also a little off the beaten path from the rest. There are three rooms in which the ceilings progress from average height to soaring. There were two exhibitions, one of self-portraits by de Chirico and Warhol, and another of a series of oversized John Armleders.

The de Chiricos—40 years of self-portraits—were striking for the ugliness of their subject matter. Of the Warhols, there were some not-very-articulated, blurry-screened paintings that have been making their way around the international fair circuit. But there was also an electric portrait in yellow and red, painted a year before Warhol’s death that was so vibrant as to appear plugged in.

The Armleders were a mixed bag, the biggest of the group painted on the floor of the gallery during renovations. When Armleders are good, they (tastefully) erupt with sculptural form as if exploding from within a 2D painted surface. When they’re not, the kitchen-sink aesthetic resembles the results of an overzealous teen drinking session gone bad. Armleder could be a poor man’s Rudy Stingel. But Caratsch’s gallery is a joy.

Caratsch’s other space (until his lease runs out in about a year and a half) had a group show of Jiri Georg Doukopil, Warhol, Araki, Condo, Armleder and Boetti. Doukopil, no matter how long he is at it, can’t seem to make a convincing body of work. The Boetti drawings, on the other hand, one a realistically rendered grid of magazine covers in pencil and another a spray-painted work, were eye-opening. Wonder if Sterling Ruby has ever taken a look.

Gmurzynska is another grand space, a three-story structure wrought in Brutalist exposed concrete by noted local architects Ruch & Partners. The gallery covers a mind-boggling array of art from acclaimed abstractionist Sylvester Stallone and photographer’s photographer Karl Lagerfeld to Yves Klein, Picasso and Leger. It’s what you might call a… challenging program.

With a little prodding I succeeded in getting Gmurzynska’s proprietor to sweep back the Old World silk curtains and reveal a trove of hidden treasures, including a small, vivid, red and fleshy portrait by Bacon, a 1927 Picasso still life and what is probably the best early Julian Schnabel plate painting, from 1981. A stunning, triangular 10-foot-tall monochromatic canvas by Richard Serra, also from 1981, looked like a charcoal black hole that had opened into the wall. It was enough to make one turn a blind eye to his celebrity stable mates. The Serra would look perfect next to a similarly hued Wade Guyton.

Elsewhere on St. Moritz’s gallery row, Patricia Low gets the prize for ballsy-ness, staging a Thomas Zipp installation and performance. (Full disclosure: I curated a group show in Ms. Low’s Gstaad space that included 1960’s Warhol flowers as well as works by Guyton, Mark Flood, Oscar Tuazon and others.) During the opening, a black-paint-smeared girl wearing no more than a mask and underpants smeared black paint on the walls. There were abstracted portraits of psychological states, each accompanied by a sculpture of a plant meant to correspond to those states. The darkness of the gallery’s interior contrasted nicely with the snow outside.

But Stefan Hildebrandt gets the award for intrepidness. He was to be found sitting in his small storefront, day in, day out, sun or snow, watching over a two-person exhibition featuring about six recent and older works by 84-year-old artist Enrico Castellani paired with works by Agostino Bonalumi, recently deceased just shy of 80, both members of the art movement Zero. Their minimal shaped canvases were on the dull side, but their presence in this small ski village is meaningful. Hats off to Mr. Hildebrandt for perseverance. And his new orange sign is nice too.

Lastly, there are St. Moritz’s éminences grises, Karsten Greve and Bruno Bischofberger. The former’s modest space is invariably dotted with dollops of Bourgeois, Chamberlain and Twombly (including, this time around, a new publication on Cy). I have always felt slightly intimidated by Mr. Greve; his is a dying breed of old school dealers, mavericks of their time (Leo Castelli, Sonnabend, Paula Cooper, Bischofsberger et al). Bischofberger is the warhorse and the gallery I admire more than any other. The legendary force of Mr. Bischofberger’s compulsive hoarding has for years had him displaying everything from Swiss folk art, Engadin furniture, historic chairs, glassware and ceramics to buildings worth of Basquiat and Warhol (perhaps you remember he was a character in Schnabel’s Basquiat film). On exhibit this time around was a group of ceramics by Miguel Barceló, probably Spain’s most successful living contemporary artist, who did a ceiling full of psychedelic stalactites for the U.N. in Geneva. The raw clay works of intersecting vessels on show at Bischofberger are not his strongest suit, but the viscous white monochrome paintings that congeal like cream floating on the surface of the canvas are delicious.

St. Moritz is an amazing little art town, and it’s much easier to get around to the galleries than it is in London. Then again, you have to do battle with a vacationing mood—I lost one group member to I’m-not-sure-what and another to a car showroom. Too bad, as there are currently studies underway that seeks to establish the effects of art in reducing hospital stays and encouraging wellbeing. And it’s a hell of a lot safer than me getting on a snowboard: especially for the other skiers.