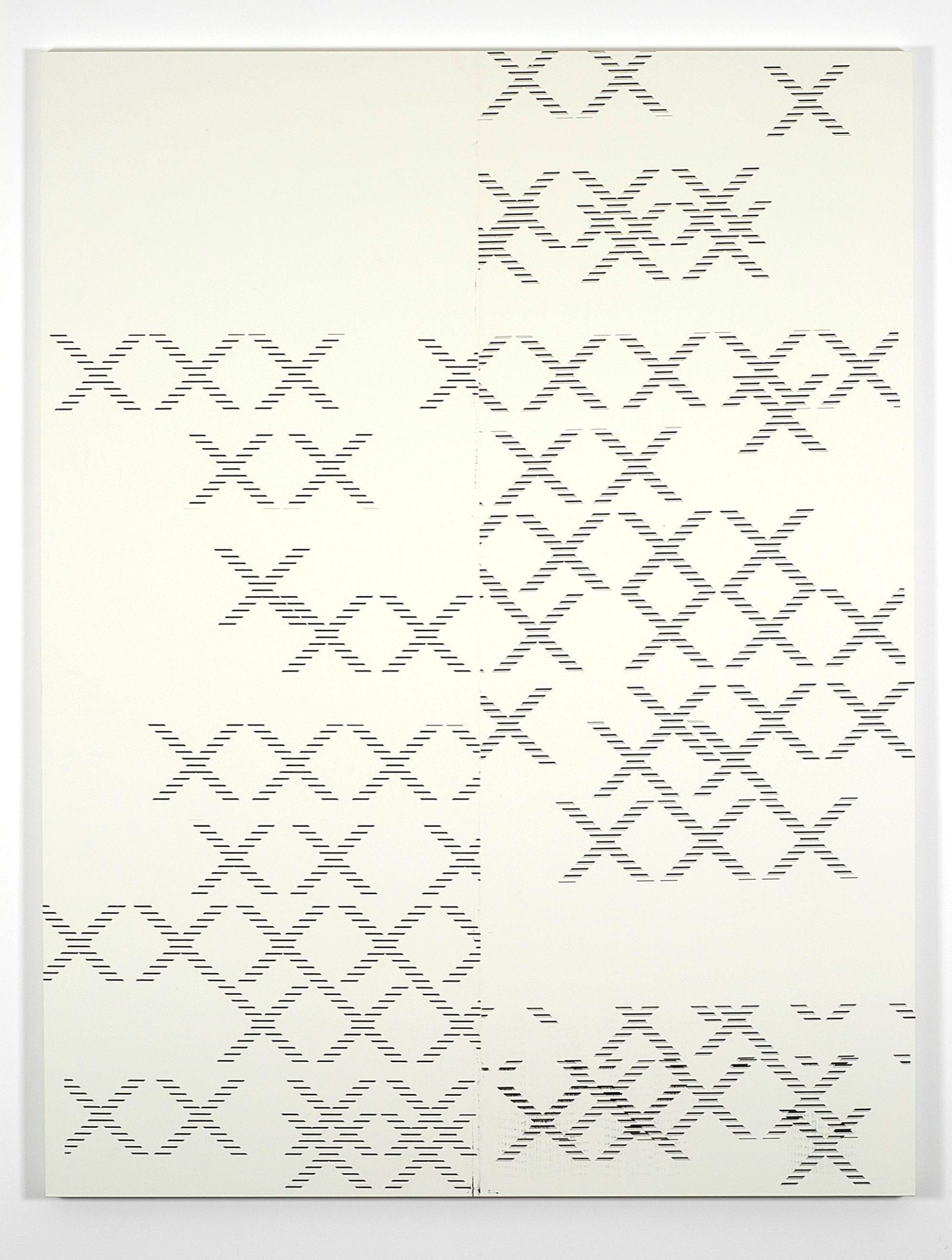

‘Untitled’ (2006) by Guyton.

Kenny Schachter is a London-based art dealer, curator and writer. His writing has appeared in books on architect Zaha Hadid and artists Vito Acconci and Paul Thek, and he is a contributor to the British edition of GQ. The opinions expressed here are his own.

As you may recall, reader, several weeks ago I wrote on this website of my travails in obtaining a Wade Guyton painting in the midst of a market surge in the artist’s work. Let’s pick up the story where we left off, back on the Eurostar, chasing a Guyton multi-X painting, this time no longer en route to Paris, but rather to Brussels. Hard as it may be to fathom, the situation got even more surreal, bringing me face to face with a degree of covetousness I never imagined existed—even I, a confirmed materialist.

The game plan was that a hapless and adorably mean-spirited collector friend of mine would accompany me to this godforsaken place—outside its charming center, Brussels can be downright Dantesque in its grimness—for no other reason than love. For me, sure, but mostly for art, and for the chase. Off we went at the ungodly hour of 6:30 a.m. to track down an elusive X in a haystack, a large-scale Wade Guyton X painting, the holy grail in the current, inflated, hyper-quick-to-judge contemporary art market.

We were met at the Brussels train station by an independent art dealer who joined us for the 60 km taxi ride to the Guyton-owning collector’s home on the outskirts of the city, a ride that, in an ominous sign of things to come, somehow turned into 110 km. Our destination was a distinctly unattractive town. I happen to be someone who celebrates the bad, but this was worse, eerie, Twilight Zone-ish. More importantly, it didn’t feel like a particularly arty place. Was this to be a wild goose chase? In the pouring rain, amidst ugly, generic buildings, a door was opened to reveal a reassuringly familiar face, one whose defining feature is an unusually prominent proboscis. Aha, I thought, so the seller was The Nose, a face familiar from any number of international art fairs and biennials.

No sooner did she appear in the door than the links in the dealing chain separating art from owner expanded, as another agent could be seen hovering behind her. The layers of intermediaries here, not counting my poor collector friend who’d been dragged out of bed just for the fun of it, were swelling to weird proportions, even for the art world. There was the owner, her agent, my friend’s agent, and my friend.

And the art—where was the art?

Ah, there it was, wedged under a heavily cracked ceiling above a stairway. You could view it from the stairwell or the landing. The lighting was meager. Even from the head of the stairs, the vantage point was too high for any kind of eye level assessment. Squinting up at this Guyton, I realized that it had already been offered to me more than once and I’d passed on it—no image had been sent prior to the Brussels trip. Then again, this made sense. We no longer reside in the past, where an over-exposed painting, one that had been offered around on the market, would be considered burned. Instead, we now dwell in a turbocharged art market—price porn is the new norm.

I was understandably uneasy about buying an artwork for just over a million dollars that had blazed across the computer screens of many an art dealer over the summer, but, still, I had to make the leap—I’d come this far, hadn’t I? I told The Nose I’d commit, which is usually all that’s required to seal the deal in the art world.

My decision was immediately chased by an unsettling feeling: had I just done something stupid?

Back in London, of course, I had other Guyton fish to fry. I’d found a small X painting. Even despite its big price, I’d had to fend off competing dealers, and in the process had to do some financial gymnastics, a kind of pre-invoice, where a friendly dealer (yes, they exist) pays for an artwork you’d like to buy before you are even invoiced, to stave off competing bids. And I’d managed to get an unheard of (for Guytons) 10 percent discount—the price was under $500,000.

And another over-offered Guyton had surfaced, for just over $1 million, in this case a single, large-scale, light-colored X that I had been offered at least four times in the past, beginning over six months ago. I’d passed on it, and passed again. It’s feast or famine locating Guytons, but an enormous gulf separates the shopped-around and haggard from the elusive, fresh-to-market works.

This seems a good enough time as any to say that overexposure of certain contemporary artists and their works is the handiwork of the jpeg jockeys, agents who cast a wide net by spreading digital images of artworks around the world. What spreads faster than the MRSA superbug virus? An art adviser hitting the send button a few hundred times after telling an owner they’d only offer a painting to one client.

This brings us to last week. Grabbing a sandwich at the Frieze Art Fair, I bumped into The Nose, who said she would like to visit my London house the following day. Since the Brussels trip, I’d harbored a suspicion that she would attempt to back out of our deal, having met her asking price for her multi-X painting, and, as it turned out, my own nose knew. Before her planned visit to my house, I was visited by the myriad go-between-ers in the Brussels deal, who shouted and threatened to sue. There wouldn’t necessarily have been a viable case, of course: as so often happens in the art world, we’d made a verbal agreement, but had drawn up no contract.

Our Belgian friend was, it seemed, suffering acutely from an all too familiar syndrome in today’s art world: greed. My doorbell never rang on that Saturday she’d planned to come by. I was stood up at the altar of art.

There is a moment that has stayed with me from that ill-fated trip to Brussels. At one point on the journey, my collector friend looked over my shoulder at the bottom line of a spreadsheet for an exhibition I was working on, and said, recalling a horse he’d once bet on, “Keep Hope Alive.”