Kenny Schachter is a private dealer and curator living in London. His latest curatorial project is a show of Paul Thek’s work at Pace Gallery that will be on view from September 25th to November 9th at 6 Burlington Gardens. The show, Nothing But Time, Paul Thek Revisited, 1964-1987, brings together works from all the media Thek used and reunites the artist with Pace Gallery which held a show for Thek in the Spring of 1966 in New York. Schachter’s catalogue essay is below:

We are all accorded an allotment in life; if you reside in the West and manage to fully live out your lifespan expectancy of eighty-two years, you will have clocked 4,264 weeks in the process. Just shy of his 55th birthday when he needlessly passed away from AIDS related illness, Paul Thek managed only 2,844 weeks. A pittance in relation to all he might have achieved and offered, but as a mightily self-actualized and fulfilled person whose legacy we all share, Thek made the most and managed to express a good chunk during what limited time he had.

Throughout his life, Thek trained himself by relentlessly pursuing and pushing traditional technical skills in draftsmanship, sculpture and installation. Nose, hand and feet studies in sketchbooks akin to the processes utilized by masters from centuries long past are imbued with finesse, individuality and acute attention to detail.

A collection of drawings in one notepad are dated December 31, 1969, as well as the 1st of January 1970, a time many of his peers might have been out celebrating; but for Thek, productivity and production were ultimately ends in themselves. So much so to the extent that striving was the only goal that mattered. That was the key to Thek’s notion of time: it’s all (very) short so best to make do, spread your seed and be as prolific as possible. Including New Year’s Eve and Day at the end of the sixties in Europe when things must have been agitated, anxious and fun simultaneously.

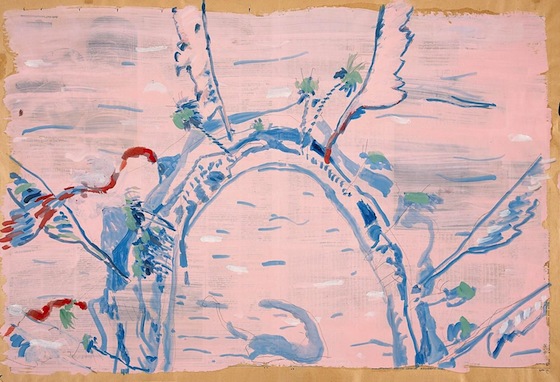

In various paintings and drawings there is a nervous, intense Van Gogh like intensity to Thek’s lines and brushstrokes, the pressure of the pencil on the paper, or brush on canvas is palpable, but it also demonstrates supreme confidence. You can also detect a forlorn sadness in some of the works, affecting compassion and empathy but also perhaps a signal of a sense of emptiness he experienced throughout his nomadic travels without ever being firmly rooted to a particular place for too long a period of time.

With Thek, there is often evidence of repetitive efforts to nail something down, a slow, steadied, patience like a turtle, sure sign of a disciplined practitioner. Thek continually challenged himself to be better, to do more, a linear approach to (ful)filling time and mastering a craft before he even introduced the conceptual into the frame. This is a lost idea upon many from the last few generations of contemporary artists unhealthily preoccupied with strategy and other unsavory aspects of what has morphed into an overly glamorous pseudo-scene devoid of content or meaning.

Today we consume far too much time on our mobile phones and ubiquitous devices, we fritter it away ever more obsessed with idle leisure, much of it spent sitting on our hands. Certainly Thek amused himself with frivolous pursuits on occasion but art supplies were never far from hand.

Thek drew or painted clocks describing their brutal functionality and the reference to loss they always portray, even titling one: “Portrait of the Artist Nude.” In front of the timepiece we are all at out most nude and exposed. There is also a very reductive line drawing with the word “MOLEHILL” written with an arrow pointing to a minor pimple of a bump in the earth, a kind of parable for our tendency to overreact to petty things rather than pulling our collective selves up by the bootstraps and getting on with it.

There are other works with fragments of angels (sometimes urinating mid flight), mythical beings that reflected Thek’s undying belief and hope in the spiritual which infused the entire pursuit of his art making, an un-blind leap of faith; faith being something Thek firmly held onto throughout his life in good times and the horrible years to follow.

Though Thek practiced (in his own quirky and customized way) and alluded to Christianity consistently in his life and work, his view of religion tended more towards acceptance and conviction through the outpouring of his own art and words.

The fealty and fidelity of Paul Thek was, above all else, an unabiding belief in laboring which had the infinite capacity to mark one’s time and space like a peeing dog. Thek made classical, elegant drawings and paintings far from perfectly rendered, with imperfect details blended with the sublime; yet still touching, beautiful and as personal as reading alone in bed.

The details of Thek can be painstakingly, excruciatingly precise such as the architecturally rendered studies of sculptures while he simultaneously excelled at what I call good bad art; in fact, Thek purposely referenced awful pieces to feed the public what they seemed to want by embracing the worst of the likes of Julian Schnabel, Enzo Cucchi, Sandro Chia and Franceso Clemente who were the rage in New York of the 1980s.

Never entirely comfortable with the notoriety early on accorded the Technological Reliquary series, Thek neither sought out fame nor to be recognized other than for his accomplishments in the multi-disciplinary realms he drifted in and out of. To be called out for one body of work that he always believed too precious was as unacceptable as unappealing. Thek wanted to be more democratic and accessible in the scope of his materials and usage.

We have all witnessed up close decay and deterioration from the onset of disease that brings us en route from the here to the there – death that is. And Thek unlike any artist before or after irrevocably froze the hair thin line between life and loss – the most dramatic, evocative depiction of oxidation, entropy, human frailty and vulnerability arrested and represented.

Thek came as close to anyone to beating time. He has touched many in the most personal and visceral way and does so in my life every day of every passing week. The tableau vivant of Thek’s Technological Reliquaries are the perfect still life come to death, a portrait of cancer literal and figurative.

Time is a life and death sentence with lots of writing on the wall as a constant reminder, a ball and chain from cradle to casket that we must make what we can and will of it. Our personal chronologies, despite how you feel about museum hanging policies, inexorably lurch forward in only one direction as sure as the sun rises and sets—we are doomed from the start.

But take heed, there is only one path forward to salvation, whatever of it there may be, and that is the endless expression of creativity in the most diligent and workmanlike manner, interacting with any and all like minded people collected along the journey.

Late in life things didn’t go particularly well for Thek, after what must have seemed like a life sprinkled early on with magic dust as a quasi-celebrated, or at least appreciated by a select few, wunderkind—young, handsome, and having experienced rapid exposure while exploring various art forms widely pursued at the time, from designing theater sets to acting in them and on TV commercials and spaghetti westerns in the 1960s.

If ever there is argument for God, Thek channeled him through his art. The spiritual spewed out of him like sage, shaman and alchemist rolled into a Socrates like, peripatetic persona of his own devise. Thek’s art and mind merged into an organic whole that he succeeded in passionately communicating to all who came into his path, or better yet, the work did so on his behalf, which despite a fair amount being destroyed for lack of resources to store, enrich and enchant still.

Things went from bad to worse after his death with next to zero support from institutions and collectors alike. Thek frustratingly equated Monet with money to the extent he even spelled it as such in his journals when writing on the similarity and shared sensibility of a particular group of paintings late in his life that Thek made from the rooftop of his East Village tenement in New York.

However, I am happy to report that after various widely celebrated retrospectives and glorious publications in the USA and Europe, this is a story with a fairytale ending that no one would have appreciated more than Mr. Thek. Even if something as vague and elusive as heaven existed, Thek would be seen sporting an apron hunched over a drafting table oblivious to the bacchanalian dancing and frolicking in the midst. And as he might have said himself, better late than never; true we all must depart, but Thek went as far as any to beat the clock.

Finally, a few words by Thek to close: “I am happy when I am efficient. Efficient at what? At producing.” Then, in the next breath he states: “I’m not interested in efficiency.” It was a sloppy, imperfect world of contradictions that Thek inhabited, but his underlying simple, sparse credo is one for all to take note of: “Don’t be philosophically incapable of action.” Enough said.