The entrance to the Saatchi Gallery on Boundary Road, where it remained in residence from 1984 to 2003

First there was the austere, New York-quoting Saatchi Gallery on Boundary Road, akin to big museum halls, large and imposing with London artist Richard Wilson’s unforgettable oil-filled room, 20:50, tucked into a corner. Wilson’s work looked even more terrifying in Saatchi’s next space, County Hall, which had served as the headquarters for the Greater London Council for years. With a great sense of the absurd, Saatchi left the paneled rooms largely untouched.

Richard Wilson’s 20:50 (1987), a room filled halfway full of light motor oil!

During his reign at County Hall, Saatchi carried on about the virtue of exhibiting in unorthodox spaces, meaning no white walls, only to revert to white walls at his current Kings Road gallery, after he was ordered out of County Hall by a judge as a result of a dispute with his landlord.

The Saatchi Gallery at County Hall

During this protracted in-between time, Saatchi launched his Saatchi Gallery website, generating something like 600 million hits a day. Seemingly by default, and without even trying once, he again touched a nerve (this time of a mass audience).

The Saatchi Gallery website

Accompanying the new gallery is a publication called Art & Music, which seems like a cross between a zine and a culture version of a giveaway homeless publication, with that sense of irreverence and disposable immediacy. In a word, it’s good.

The new Saatchi publication, Art & Music

Saatchi is not a collector in the classical sense, as everyone in the art world knows. He’s more of a trader, or perhaps he should be called a new form of public collector with a short attention span. Yet, we have all benefitted from his obsessions, however brief their appearance has been.

A quirky impresario who used to hide from the press and still hides from his own openings, Saatchi nevertheless remains a consummate showman, adman and huckster. He was part and parcel of the marketing and funding phenomenon that helped to create Brit Art, and without Charles there would be no Damien as we know him, for better or worse.

Since the 1970s Saatchi has been crafting clever deals and partnerships that have continued unabated to this very day. He’s still very much on the look-out. Arriving one morning for a student art critique, I encountered on the scene, before finding even a single teacher or student, Charles Saatchi.

The signature Saatchi collecting method, as many call it, is the lump and dump: buy things cheaply en masse, the good, bad and ugly, then sell in the same fashion at auction, usually after a brief holding period. Some spaghetti could usually be expected to stick to the wall. His earliest use of the tactic, involving Chia, Clemente and Cucchi, was seen to have irreparably damaged careers, which from hindsight seems a prescient instance of de-accessioning.

The addition of chef Nigella to the stew only complements his appeal.

In the early ’00s, prior to opening his latest incarnation of a gallery, Saatchi seemed to become less relevant in a world of exploding hedge funds and artists wielding private planes rather than brushes. Hirst traded in art for economics and seemed to want to best Charles at his own game (hunting).

But Hirst the collector was more callow, acquiring art by stars and studio assistants rather than truly ferreting out talent. Whereas Saatchi prowled the world over with perseverance and tenacity, Hirst piled on Bacons and the like at public auction, and for a brief time his extravagance trickled down, affecting the rest of the marketplace, in a small way in relation to Saatchi historically.

You make money selling art and create wealth keeping it: if Charles Saatchi had held on to more, he might have found himself in the same tax bracket as Hirst. But in the end, that doesn’t seem to be what drives Saatchi. Rather, his aggrandizement seems to be a modern version of a classical patron, or enabler for art, artists and the public to engage.

Whatever his true motivations — and without a doubt a passionate love of all things art is at the forefront — we are all the beneficiaries.

Charles Saatchi and Nigella Lawson in a London gallery, 2003

The new Saatchi Gallery housed in the grand Palladian-style Duke of York HQ, is a sublime group of rooms with real generosity of spirit and freedom, offering the liberty to touch (even though you are not supposed to), smell and see art works up close and from afar, as they were made to be seen, with little interference from the architecture, ungainly barricades or multitude of imposing guards.

The place has 13 galleries, which in this instance is a lucky number, as the spaces are plentiful, well proportioned and full of light; at the same time, the layout is fractured and deceiving. That is the real continuing revolution, Saatchi’s hybridization of space, his manner of collecting and public presentation of works, which accounts for a meaningful shift in the experience of art.

The Saatchi Gallery today, at the Duke of York HQ in Chelsea

The Duke of York HQ was formerly the Royal Military Asylum for the Children of the Soldiers of the Regular Army. How chaotic it must have been with 1,000 orphans — 300 girls and 700 boys — living in an atmosphere probably not unlike that of the inaugural exhibit, filled with wildly inconsistent and oftentimes juvenile Chinese art from the Saatchi collection.

The Saatchi Gallery today, at the Duke of York HQ in Chelsea

Presumably the title of the first show, “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China,” Oct. 7, 2008-Jan. 18, 2009, refers to an extension of the rebellion engendered by the Tiananmen Square demonstrations, which gave rise to the pro-democracy movement. However, the title could just as easily refer to the Cultural Revolution, when China was expunged of liberal tendencies in society, like good art.

Saatchi’s Chinese collection resembles nothing so much as a potpourri of flotsam and jetsam readymade for the consumerist West. A new sculpture by Zhang Huan (b. 1965), the celebrated “East Village” performance artist who now splits his time between Shanghai and New York, features a stuffed donkey having intercourse with a model of the (formerly) tallest building in China, with a huge pipe representing the ass’ phallus. This “kinetic” sculpture was thankfully not functioning at the time of my visit, which was fairly late into the course of the exhibition. Aren’t we well past the stage of such boorish antics? Apparently not.

Zhang Huan, Donkey, 2005. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

Zhang Huan, Donkey, 2005. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

Also on hand are several multimillion-dollar “Bloodline” paintings by Zhang Xiaogang (b. 1958). Seeing such a grouping of these large-scale works was enlightening: no matter how you draw it, the bloodline paintings are homogeneous and, after a very short while, dull. And the pile of faux shit by the Beijing artist Liu Wei (b. 1972), entitled Indigestion II (we are thankfully spared the first iteration), referred to in the exhibition pamphlet as “a monumental poo,” was comprised of detritus including toy soldiers, which can be taken as a protest against rising militarism. All that was missing was some steam.

Zhang Xiaogang, A Big Family, 1995. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

Liu Wei, Indigestion II, 2004-05. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

The formulaic and (allegedly) anti-consumerist paintings by the Beijing-based painter Wang Guangyi (b. 1956 or ’57), carry slogans reading “Porsche NO” and “Materialist’s Art,” among other sentiments. Being a go-carting enthusiast, one wonders if Saatchi was attracted to the Porsche work simply as a statement about his automotive tastes. To the average sensibility, these comments on contemporary materialism are heavy-handed and obvious. How tedious it must be to have to experience these pieces for longer than a cursory glance.

Wang Guangyi, Porsche, 2005. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

One of the more successful works was Old Persons Home by the collaborative, Peking-based team of Sun Yuan (b. 1972) and Peng Yu (b. 1974). Not for the silly reason stated in the booklet: “these controversial artists work in extreme materials such as human fat tissue, live animals, and baby cadavers to deal with issues of perception, death and the human condition.” Yawn.

Rather, the somewhat obvious work comprised of lifelike figures of decrepit, old political leaders cast in latex, randomly rolling around in self-propelled wheelchairs colliding into each other, was so enticing because gallery visitors are allowed unimpeded entrance to the free-for-all crash-up. After seeing the piece, you will never look at an aged person in a wheelchair the same.

(And for some wholly inexplicable reason, the Chinese wheelchair derby was still up and running during the subsequent Middle East show, kind of like a stand-in for Saatchi himself.)

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Old Persons Home, 2007. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”.

Saatchi Gallery.

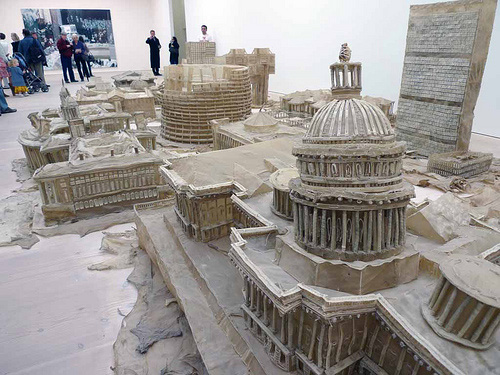

The sprawling installation by Liu Wei (b. 1972), titled Love It! Bite It!, was a labyrinthine model city in a state of deshabile (and including a model of the White House and the Guggenheim Museum), all built out of edible dog chews, beige in color. Similarly, in the many Ron Mueck-esque hyper-realist sculptures of both Cang Xin (b. 1967) and Xiang Jing (b. 1968), the art was bad but all of it could be seen up close and unhindered by typical museum rules.

Liu Wei, Love It! Bite It!, 2005-07. “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China”. Saatchi Gallery.

Cang Xin with his work, Communication (2006), in “The Revolution Continues: New Art from China” at the Saatchi Gallery

Overall, “New Art from China” suggests that Chinese artists certainly like the notion of the gallery-as-circus. As does Saatchi himself.

Saatchi isn’t thinking too hard when it comes to exhibition concepts, what with this fairly dim curatorial notion of shows whose roster is set by nothing more than common geography: China first, then the Middle East and India and Pakistan. This “It’s a Small World After All” approach to international relations may not be very realistic, but it works, at least as far as the art market is concerned.

Then there is the partnership with the auction house Phillips de Pury & Co., which provides for free admission to the Saatchi Gallery. Prior incarnations all came with a high entry fee attached, but now Phillips has stepped in to subsidize access. Though happy as the next person to pocket the pounds, by the time I reached the top floor “Phillips de Pury ” Company Gallery,” I was less certain this was quite such a deal.

The “Untitled (Chinese Paintings)” of Julian Schnabel were billed as “a serendipitous coincidence that the ground of this image” — a faint image of a seated Chinese Buddhist figurine of some sort — “happens to come from a Chinese mirror that Julian found 20 years ago for his then wife.” Yes, how serendipitous, to plunk these works in the middle of a show of Chinese art.

Julian Schnabel, Untitled (Chinese Painting), 2008. “Julian Schnabel – Untitled (Chinese Paintings)”. Saatchi Gallery.

Just when we thought he couldn’t get worse, we get a glimpse of Schnabel the Orientalist. On some level, I’d rather pay admission than view such crap. Because without Phillips, we probably wouldn’t have it, since Charles bailed out of Schnabel some time ago.

“Perspectives: Arab and Iranian Modern Masters,” which followed Schnabel’s “Chinese Paintings” in the Phillips gallery, is organized by Sheikha Lulu al-Sabah, Phillips’ Middle East specialist, and is a much more cohesive and informative undertaking. While Saatchi was a bit slow with his embrace of all things Chinese, his embrace of Middle Eastern art is timelier, and helps to cast a net of coherence over an area that has seemed rather too busy with other things to join the international avant-garde.

“Perspectives: Arab and Iranian Modern Masters” in the Phillips de Pury & Company Gallery at the Saatchi Gallery.

Hussein Madi, Tarab, 1997. “Perspectives: Arab and Iranian Modern Masters”

Phillips de Pury & Company Gallery, Saatchi Gallery.

Thus the Saatchi Gallery’s second show, “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East,” Jan. 30-May 9, 2009, presents works by more than 20 young artists, and turns out to be a breath of fresh air, albeit a politically charged one. Here we see Saatchi the good Iraqi Jew with a mind as open as his wallet. Nevertheless, the exhibition presents a beautifully installed esthetic of horror, chock-a-block with Guernicas and Screams. In “Unveiled,” Saatchi masterfully manages to commodify war and strife but does so with eloquence and elegance.

One impressive installation, by the French-Algerian artist Kader Attia (b. 1970), presents a phalanx of hollow, tinfoil apparitions in the form of burka-clad kneeling women, in what could be a pose of prayer. The large, long room is filled with 24 rows of 11 figures, totaling 264 ghost-like figures in a massive grid. Instead of faces, there are empty black holes. Though impressive, with a sense of mourning and dread, the work was also a little bit ridiculous, suggesting an elaborate field of Jiffy Pop or perhaps baked potatoes ready to explode.

The sculpture was made on site by wrapping scores of women with foil. Female guards from the gallery were asked to serve as models for free, while additional women from off the street were hired at £80 per head. This involvement of spot labor was reminiscent of the annoying antics of Santiago Sierra, and nearly ruined the work. But then again, at least it employs women in a public capacity, bringing however indirectly some sexual liberation to the notoriously sexist Middle East.

Kader Attia, Ghost, 2007. “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East” Saatchi Gallery

The paintings of the Iranian-American painter Tala Madani (b. 1981), whose candy-colored parodies of male domination in her native Iran are currently on view at Pilar Corrias in London, would do better in a show of more assorted nationalities, which I strongly suggest Saatchi contemplate next. She favors a cartoonish but painterly style, rendering men praying in pink maillots or massed in groups, holding their hands over their ears. In this instance I recommend bypassing the corny capsules in the Picture by Picture Guide, which can be had for £1.50, a new staple of the Saatchi program, lest it soil an immediate attraction to these works.

Tala Madani, Nosefall, 2007. “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East”, Saatchi Gallery.

Wafa Hourani (b. 1979), a Palestinian artist who lives and works in Ramallah, has constructed a model-sized cinderblock refugee camp, complete with electric lights inside the shacks and twisted wire antennae above them. Watchful Israelis peer over impossibly high cement walls, replete with mirrors so inhabitants can wallow in their own despair. An Israeli water park lies on other side of the grim wasteland. This work is a hammer-over-the-head metaphor for oppression and subjugation but at the same time it strongly brings to mind a kind of political entropy.

Wafa Hourani, Qalandia, 2007. “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East”, Saatchi Gallery.

As the art world is thoroughly global, Saatchi can be forgiven for seeking, as was seen in his China show and as is the case here, new artworks that may resemble foreign pastiches of his previous favorites from the U.K. Thus, the Iranian artist Shirin Fakhim, who shows with something called the Ministry of Nomads in London, is like a Middle Eastern Sarah Lucas. Her sculptures consist of figures made from stuffed stockings wearing loads of lingerie, replete with bulbous fruits for breasts, called Tehran Prostitutes. Surely one such maker of stuffed female mannequins is enough — though perhaps these sculptures actually mean something in the Islamic Republic.

Shirin Fakhim, Tehran Prostitutes, 2008. “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East”, Saatchi Gallery.

Similarly, Saatchi’s affection for art with a certain shock factor — or is that schlock factor? — is supplied by the cheesy photoshopped expressions of transgendered sexuality by Ramin Haerizadeh (b. 1975), whose works have been displayed at Art Dubai and sold at auction (though not for more than $10,000). Haerizadeh’s color photographs of distorted, tattooed hairy fat men in seraglio are an all-too-obvious statement in the face of regional repression.

Ramin Haerizadeh, Men of Allah, 2008. “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East”, Saatchi Gallery.

As if to prove that he is never still, Saatchi has released an all-points bulletin: he plans to front a new TV show searching for the next art star — don’t we have enough of those already? — ingeniously titled “Saatchi’s Best of British.” Though he won’t speak directly to the camera, he will be depicted in each episode surveying the lay of the land. After all this time, the “notoriously shy” mogul is finally, I suppose, admitting to his own Paris Hiltonitis. The Wizard of Oz is coming out from behind the curtain, as is shown as well by the fact that his name is plastered all over Duke of York Square in banner after banner. How difficult it must have been to keep up the ruse of diffidence all those years.

From dog shit and donkey to tranny and tyranny, Saatchi loves the tasteless avant-garde gesture. But in tandem there is always a glimmer of awe and a sense of risk-taking that something could go terribly wrong. One hopes that the initial two shows at the new gallery do not represent Saatchi’s sole take on art today, as something so easily pigeonholed. But Saatchi’s constant restlessness should at least keep things lively.

First Hirst, then the museums, the website, magazine, TV show (!) and the culmination of it all in Duke of York Square: together we are left with a residue of a vision, an illumination, albeit an inconsistent one, of the temperature of contemporary art today. The rest is for you to decide.

Kenny Schachter

Click here to see the original article directly on the artnet news website